Perimenopause / Menopause Nutrition

Nutritional Status

Nutritional status looks at a person’s health through the lens of nutritional intake, absorption and system utilization (Lee, 2010). An investigation into nutritional health is done through several lenses including Body mass index, body composition using weight, height and body mass measurements and blood tests can measure nutrients within blood (Barbosa-Silva, 2008). It can be a measurement for overall health and highlight health issues such as anaemia, chronic diseases, malnutrition, growth and hormone issues and cognitive functioning (Ghazi et al., 2015). Inadequate nutrition intake or absorption effects all body systems and results in poor health, there are key periods within the lifespan where nutritional needs increase such as pregnancy, childhood, over 65 years and perimenopause / menopause and old age (Kostecka, 2014: Christie & ND, 2023).

Nutritional status assessment for menopause would be beneficial to prevent osteoporosis, chronic systemic inflammatory diseases, and early cognitive decline (Devarshi et al., 2021). Declining levels of estrogen and progesterone impacts the absorption of key nutrients such as magnesium, zinc, copper, and calcium in osteoporotic health (Nordin et al., 2004). Assessing a women’s nutritional status can highlight future risks for both disease and weight gain. It is an opportunity to raise awareness of a healthy diet and its impact on longevity and functional, independent living into old age (McBurney et al., 2021: Mahdavi-Roshan et al., 2015).

Menarche starts at around 12 years of age and may be a good predictor of a female health into old age. Studies have shown early onset menarche is associated with social stress, complex family dynamics and abuse, particularly sexual abuse. Conversely late onset of menarche is associated with low bone density, depression and exposure to war torn countries. The reproductive cycle experience is thought to be a blueprint for future diseases. Research has shown that smoking and psychosocial stress, PCOS are good predictors for early, complicated perimenopause, these factors are more likely present in females who had early menarche, assessment is important as research has shown that premature menopause increases the risk of heart disease and osteoporosis (Forman et al., 2013: Bae et al., 2018: World Health Organization. 1994: Salminen et al., 2006). Assessments would be done based on the symptoms and complaints of the patient (Nemati & Baghi, 2008).

Dietary Assessments:

Dietary assessments can evaluate nutritional intake and highlight key deficiencies or imbalances such as iron, B12 and folate causing anaemia (Thomson et al., 2011). A variety of methods may be used depending on the patient and their lifestyle. The most common used methods are food frequency questionnaire a food diary or 24-hour recalls. One study found patterns linking high quantities of omega 6 & 9 intake with depressive symptoms in menopausal women (Li et al., 2020). The benefits of dietary assessment are that they are relatively inexpensive, non-evasive and used for goal setting by adjusting and repeating according to progress, as well as assessing the effectiveness of the intervention (Dao et al., 2019). They can be used to build a holistic profile of the patient, providing detailed sensitive information around food behaviours including the types and amounts consumed, as well as the wider causations / triggers; including social norms, environments and social / psychological factors (Dixon et al., 2021: Lafrenière et al., 2018 Frankenfeld et al., 2012). This can raise conscious awareness of eating behaviours for the patient so that they may access support for behaviour change and identify nutritional gaps and imbalances (Shim et al., 2014: Young et al., 2019).

The disadvantages to dietary recall is that human error risk is high, memory lapses and blind spots are inevitable, as well as consciously under reporting for fear of judgement (Hebert et al., 1997: Hebert et al., 1997). The assessment tool may not cover all foods and cultural differences making comparisons difficult across populations & they can be time consuming taking considerable effort to record accurately (Harrison et al.,2000: Klesges et al.,1995).

Anthropometric Assessments:

Body composition measurements include Body mass index, waist circumference to measure abdominal fatness in menopausal women as an indicator for metabolic diseases, Skinfold calliper thickness measurements of subcutaneous fat in a variety of body locations can estimate overall body fat percentage and chronic disease risk (Van Pelt et al., 2001). Bioelectrical impedance Analysis uses electrical currents to estimate body fat, muscle, and bone density through resistance to the current (Dehghan & Merchant, 2008). DXA imaging Xray was first used for Osteoporosis screening, particularly in Menopause / postmenopausal women (Albanese et al., 2003), measurements conducted by a professional, can identify composition changes such as obesity and low muscle mass, this is then used to develop appropriate interventions such as dietary advice, and supplementation of Calcium and Vitamin D and in some cases Biosphonates to slow the rate of bone breaking down in Osteoporosis (Sunyecz, 2008).

The benefits of body composition measurements using skin callipers and fat mass scales is that they can be used in clinical and community settings, and they can be used for baseline clinical measurements at the start and end of an intervention to evaluate the effectives (Svendsen et al., 1993: Maillard et al., 2016). However the measurements are thought to be crude and do not take into account individual body shape / type composition factors, it is prone to error, variability due to the measurements likely taken at different times, by different practitioners, with varying hydration level and food intake. Overall, they are useful to use in conjunction with other assessments and use to build a picture alongside wider information to identify health risks ( Heyward, 2001).

Biomedical testing

Biomedical nutritional tests measure blood and fluid for specific nutrients (Sauberlich, 2018). One study showed how biomedical testing can detect raised homocysteine and low vitamin B12 and folate associated with osteoporosis, the tests can be used to diagnose conditions and the severity with accuracy, before symptoms occur (van et al., 2011: Jamil et al., 2015. Blood tests can be used to assess treatment outcomes. Some tests can predict the likelihood of diseases such as cholesterol testing to predict heart disease (Artiss & Zak, 2000). Disadvantages are false positives, the tests can be expensive for multiple tests, and are invasive (Butler et asl., 2022). Routine bloods to check FSH levels and to rule out other endocrine issues which mimic perimenopause symptoms are used in some cases (Uehara et al., 2022). Nice guidelines state Pelvic examinations should not be performed routinely, blood tests to check elevated FSH level on two blood samples taken 4–6 weeks apart is recommended, to rule out other endocrine disorders and confirm menopause, although this controversial (McNamara et al., 2015).

Functional Assessments

Functional nutrition deficiency assessments of strength, endurance and balance during daily activities can evaluate biochemical and physiological functions. Physical tests of muscle control, depression, vision impairment and lip cracks can highlight vitamin and mineral deficiencies (Reber et al., 2019). The tests can be used to identify autoimmune diseases or metabolic imbalances and guide personalised interventions: (Picó et al., 2019). They do require specialist training, are costly and used as part of a wider picture (Maltais et al., 2009).

Perimenopause /Menopause nutrition

Menopause is defined by the absence of a women’s period for 12 months consecutively marking the end of the reproductive stage in a women’s life (Brett & Cooper, 2003). Perimenopause is the biological transition stage, where hormonal changes occur. This typically starts in a women’s 40’s but can happen at any age and may continue for 2-11 years (Burger et al., 2007). During this time many hormonal changes occur, effecting women in a variety of physical, mental and emotional ways and the severity of symptoms varies widely based on many factors such as stress and nutrition (Karaçam & Şeker, 2007: Prior, 2019). It is important for women to understand the signs and symptoms of menopause so in order to seek support with symptoms which can cause significant disruption to normal daily living (O'Reilly et al., 2022) Whilst some women move through this stage with little or no notable symptoms, for many the transition can be a bumpy ride which requires research into signs, symptoms and the factors which exacerbates them (Zhu et al., 2022). Signs and symptoms include hot flushes and night sweats known as Vasomotor symptoms, disrupting sleep patterns setting of a cascade of mental and physical side effects from lack of sleep such as anxiety, depression, hormonal mood swings, weight gain and the inability to make good decisions and manage daily responsibilities effectively, often effecting relationships and careers (Harper et al., 2022: Chiu et al., 2021). Research has highlighted that women experience feelings of failure and feel unable to perform well at work which has caused many women to leave their careers during this stage, tthere has been an increase of campaigns to provide women support at work and the opportunity to take menopause leave (Mulla, 2023). Other symptoms include muscle aches, pains and headaches, Painful irregular and prolonged heavy periods, skin changes, palpitations, vaginal dryness, loss of libido and discomfort during sex and increases in urinary tract infections and for a small minority severe depression and anxiety (Willi & Ehlert, 2020). Awareness of the symptoms has empowered many women to get the help they need from G.P’s and increased the interest and funding for research into both women’s health in general (Jermyn, 2023). G.P’s have swiftly moved from prescribing medications for depression and anxiety due to a lack of awareness of menopausal symptoms, to testing for menopause and prescribing hormone replacement therapy (HRT) where appropriate (Newson, 2021). Whilst HRT is not suitable for every woman, some women may take months to find a suitable type and dose, and research has highlighted that Progesterone can negatively effect mood disorders further (Vigneswaran & Hamoda, 2022), it has enabled around 1 million perimenopausal women to reduce debilitating symptoms to function daily and fulfil their responsibilities (Green et al., 2019). Women have previously reported ending their careers, long term relationship breakdowns and experiences of erratic mental health with little support, understanding or intervention (Converso et al., 2019: Mulla et al., 2023). One study found that for every negative symptom experienced employment rates fell by around 2 percentage points, the main symptoms cited were psychological distress, often exacerbated by the job and feelings of worthlessness and incompetence leading to burnout (Bryson et al., 2022).

The effects on the NHS and economy are considerable, The British heart foundation state that cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of mortality and 24,000 women of menopausal age (50) in the UK die each year of heart disease (Hamoda et al., 2022). Osteoporosis risk is accelerated during menopause putting women at high risk of the disease due to having a lower peak bone mass than men as well as reduction in estrogen. According to the National Osteoporosis group 536,000 fractures are attributed to osteoporosis each year in the UK (Kimpton et al., 2021). There is however a concern that women taking HRT to feel normal are able to continue with poor nutrition, little exercise, high stress and over consumption of alcohol, increasing their risk of mortality, osteoporosis and inflammatory diseases (Yoshany et al., 2022). There is considerable research highlighting that women who avoid alcohol, eat a Mediterranean style diet, exercise daily, increase efforts to reduce stress and engage in healthy habits such as cold water swimming, walking in nature and Complementary Therapies significantly reduces menopausal symptoms (Marlatt et al., 2022). During perimenopause estrogen levels fluctuate, leading to changes in body composition, effecting metabolism, bone and heart health ( Ko & Jung, 2021). General nutrition guidelines do not consider the changes of this stage in the life span and therefore additional information for women to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, obesity and cancers is required (Yelland et al., 2023). perimenopause is a unique stage of life which requires key nutrients for health (Christie & ND, 2023).

(Marlatt et al., 2022).

Glucose resistance and weight gain

Insulin sensitivity is known to reduce during this time, putting women at risk of metabolic diseases and obesity and increasing the risk of chronic diseases (Gianos et al., 2023: Pérez-López et al., 2020). On average women gain 5-7 pounds during the menopause journey. Weight gain around the abdomen (visceral fat), and changes to HDL function is a risk factor for atherosclerosis (Nasr et al., 2022). Studies have shown during the latter stage of perimenopause women tend to have higher levels of chronic pro-flammatory cytokines, abdominal obesity, triglycerides and cholesterol (Chedraui et al., 2014). A low glycaemic, high fibre including omega 3’s diet could help to prevent obesity-related diseases (Pallazola et al., (2019).

Vitamin absorption

Studies have shown women to be less efficient at utilizing and absorbing nutrients especially Vitamin D and B12 (Bailey et al., 2022). Women should have B12 levels tested and aim to consume 2.4ug per day of fortified foods or supplements (O'Connor et al., 2016). Other key nutrients should be assessed are Calcium intake recommended to be 1000mg/day and 800 IU/day of Vitamin D, at least 1g/kg body weight of protein. Iron levels can be assessed if heavy prolonged periods occur with fatigue symptoms, women should be consuming at least 14.8mg/day (Jane & Davis, 2014: Küçük & Ertan, 2008). it is also important to avoid Iron overload which researchers suggest may contribute to hot flushes and Osteoporosis, as we age we reduce the efficiency of offloading excess iron (Jian et al., 2009)

Inflammation

As estrogen declines through the menopause transition, natural aging low grade inflammation occurs (Marlatt et al., 2022). Estrogen is a natural anti inflammatory and protects against oxidative stress and ischemic damage and therefore neurodegenerative disease (Behl et al., 1995). The decline exposes women to deteriorating numbers of T and B cells reducing the capacity to respond to pathogens and predisposing women to auto immune diseases such as Rheumatoid arthritis (Angum et al., 2020).

Women become more susceptible to inflammation at this stage of life and need to adapt their diets accordingly (Feskens et al., 2022). Hot flashes, mood swings and joint pain are symptoms of inflammation which could be reduced by eating a Mediterranean diet high in fruits, vegetables, oily fish to increase anti-inflammatory omega 3’s and reduce ultra-processed foods known to increase pro-flammatory cytokines which encourage autoimmune diseases (Barrea et al., 2021: Nestares et al., 2021). Vitamin D decline also effects the immune system due the role in producing antibacterial peptides stimulating macrophages to eat bacteria (Min et al., 2021).

Bone Health

Calcium, Vitamin D and magnesium are critical for bone health, during perimenopause estrogen levels decline leading to loss of bone density as well as a decline in vitamin absorption leading to increased risk of osteoporosis post menopause. Osteoporosis affects one out of three postmenopausal women, with an annual bone loss of 2–3% during the first few years and 0.5–1% thereafter (Malabanan & Holick, 2003.:Rizzoli et al., 2014). HRT is evidenced to reduce the decline of bone fragility and sarcopenia (Marty et al., 2017), however, research has also shown that HRT reduces the ability to absorb key nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, Vitamin D, B complex and zinc (Barrea, et al., 2021), therefore nutrition (particularly calcium and protein intake, but also vitamin D, potassium, phosphorus and other micronutrients and macronutrients), regular weight-bearing exercise, smoking cessation (where appropriate) and reduced alcohol intake is recommended (Weaver et al., 2016). Musculoskeletal pain increases during menopause due to the decline in Estrogen which has a role in cartilage metabolism, and bone maintenance (Bei et al., 2020). Sarcopenia speeds up with age, during menopause muscle weakness, and loss is accelerated with inconclusive data on improvement with HRT use (Khadilkar, 2019). A low GI pro inflammatory diet is evidenced to reduce muscle turning to fat alongside resistance training (Cacciatore et al., 2023)

Menstrual cycle

During perimenopause women often experience heavy painful periods which are often extended and cause iron deficiency or anaemia (Samuelson Bannow, 2020). Increasing leafy green vegetables, poultry, lean red meat and beans to increase iron would support the women’s energy levels and ability to cope with the symptoms (Ciebiera et al., 2021).

Mental Health and Sleep

Perimenopause is a demanding time biologically, physically, and psychologically. Mood fluctuations and a reduced ability to control emotions and emotional outbursts. In some cases, severe anxiety or depression is experienced. Magnesium, omega 3 and vitamin B6 are key nutrients to support brain function reducing to mood disorders (Businaro, 2022). Depressive disorders are a common symptom of perimenopause likely due to the Estrogen and serotonin pathway. Women with a history of premenstrual syndrome or postnatal depression have a higher occurrence (Soares, 2019). A reduction of quality sleep can increase depression and anxiety symptoms and significantly affect obstructive sleep apnoea, restless leg syndrome, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other inflammatory diseases (Medic et al., 2017: Dey et al., (2022). Magnesium, omega 3 and vitamin B6 are key nutrients to support brain function reducing mood disorders and reducing the risk future Dementias (Sliwinska & Jeziorek, 2021). Vitamin B12 is important for brain and red blood cell function support energy levels and mood stability (Kumar et al., 2023). B-Vitamins and vitamin C, D,E and omega 3 are associated with good cognitive health as omen age (Bruins et al., 2019).

The Mediterranean diet is evidenced to be beneficial for perimenopause due to its 0 ultra-processed consumption and a wide variety of high fibre plant based whole foods, as inclusion of balanced protein, fats and low glycaemic carbohydrates, leading to an abundances of nutrients and minerals consumed Flor-Alemany, et al., 2020). The diet has shown a significant reduction in menopausal symptoms, as well as a reduction in cardiovascular diseases, metabolic symptoms, osteoporosis, weight loss and improvements of mental health. Recent research has shown the wider the variety of plant based foods consumed the more versatile the gut microbiome which promotes good health via every body system (Silva t al., 2021

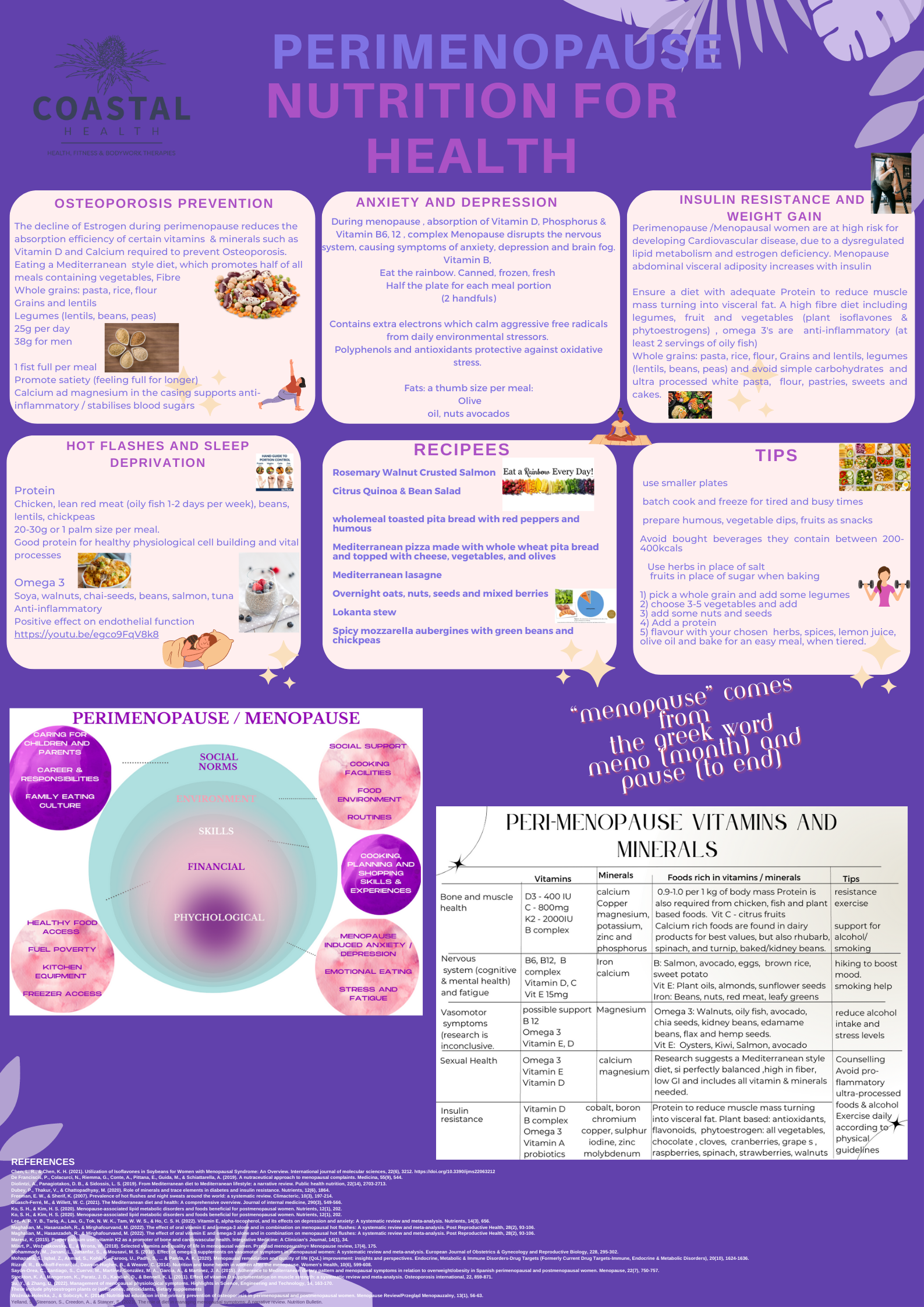

When designing educational or awareness material, there are many factors to consider in order to gain maximum reach and benefit for the targeted population Gebbels, 2023). Considerable research into what is already known, what has been tried and the outcomes / evaluations of behaviour change, rather than champaign reach is required (Adler & Ostrove, 1999: Suarez-Almazor, 2011). In this case nutritional requirements for health during peri menopause / menopause. Persuasive health messages include a threat message e.g. if I do not eat a healthy diet I increase my risk of Osteoporosis, followed by a self-efficacy message, but if I eat a Mediterranean style diet I will reduce my risk and feel and look healthy, followed by motivating cues to action (Witte et al., 1995) Utilising information around the barriers women face for nutrition, how women of this age and time of their lives digest information (Cronin et al., 2021). Barriers to good nutrition range from socioeconomic factors, cooking skills, awareness, and time as well as psychological factors such as stress and emotional overload (Fenton et al., 2023). Furthermore, it is important to normalise menopause and increase positivity of this stage of life, as opposed to treating it as a disease which needs to be fixed medically (Hunter et al., 2020). Messages of behaviour change to support health longevity and embrace this normal stage of life is key (Hickey et al., 2022).

Socioeconomic

Humans have varying physical, economic, and sociocultural experiences and therefore food buying choices and opportunities which effect health and wellbeing. So called low socioeconomic status women may live on or below the poverty line often have less access to healthy food choices (Hastings et al., 2000: Jayasinghe et al., 2022). Moreover, they are likely to live in a community where fast-food shops are plentiful and fresh healthy whole food options are less available, known as a food desert (Reid et al., 2021). A lack of time, money, choice, support, and opportunity is common within low socioeconomic groups living in often difficult living conditions, working long hours, with limited health, financial, support and opportunities, leading to higher levels of stress and mental health issues (Blundell et al., 2022: Darmon & Drewnowski, 2008). Minority groups are also at higher risk of experiencing health inequalities, affecting the healthcare, education and social support received (Stanzel et al., 2021). It is well evidenced that processed foods are less expensive and more convenient (Gupta et al., 2020). Current Government interventions for women classed as low SES are behaviour change support which has leaned towards educating the individual through theories such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour to support self-efficacy and changing attitudes toward healthy food choices (Povey et al., 2000: Djojosoeparto et al., 2022). Mobilising social support is costly and ineffective if the environment is not also changed through policy to address inequalities. (Darmon & Drewnowski, 2008). Universal structural environment food policies and media campaigns are deemed gold standard to reduce health inequalities for individuals (Caraher & Coveney, 2004). Studies have evidenced how individual social status is further influenced by exposed media. Lower SES groups have a higher exposure to targeted advertising of cheap fast foods and misinformation affecting food choices, which reinforce the media feedback loop. This digital divide is widening the inequalities gap (Kumanyika & Grier, 2006). Moreover menopausal women classed as low SES and minority groups are known to be at higher risk of non-communicable diseases and experience a wider range of symptoms and often those symptoms are more severe (Namazi et al., 2019: Yazdkhasti et al., 2015). Social inequalities create a chronic cycle difficult to overcome and increase challenging menopausal symptoms and further risk of conditions such as osteoporosis, cancers, diabetes, and dementia (Steenson & Buttriss, 2021: Biasini et al., 2021: Namazi et al., 2019).

Time

Time in the modern-day society is a considerable barrier to good nutrition (Chopra et al., 2019). Women are working longer hours and have constant stimulation 24/7 from technology (Toklu & Nogay, 2018). Perimenopause comes at an age where women often have young children who require support with homework, sports and music clubs and increased childhood social lives (Thomas et al., 2018). Women are likely to be at the height of their careers as a high percentage of women share an equal financial responsibility (Ballard et al., 2001). This is also a stage of life where women’s parents often need care, as their health declines, this leaves less time for meal planning and positive eating behaviours (Woods, 2022: Khandelwal, 2020). The poster should therefore include tips and simple meal recipes for busy menopausal women.

Stress and mental health

The high demands and responsibilities such as family, career and biological stressors placed upon this cohort of women can create considerable emotional stress (Gadgil & Kulkarni, 2019). Vasomotor symptoms, decreases in melatonin, fatigue, mood disorders, anxiety, and palpitations as well as erratic and often painful periods are widely reported (Verde et al., 2022: ogervorst et al., 2022: Converso et al., 2019). Sleep deprivation is evidenced to increase sugar cravings and poor food choices and furthermore, women report a lack of mental energy to plan and shop well for nutrition (Stute & Lozza-Fiacco, 2022). Ultra-processed foods positively affect the reward circuit, making them psychologically addictive, creating weight gain, increased waist circumference and insulin resistance (Azeredo et al., 2021: Gill et al., 2022). Emotional and stress eating during this stage may also be contributed to difficult psychological changes women go through around self-image.

(Süss & Ehlert, 2020). Changes to body shape, skin texture and signs of ageing may raise awareness of personal mortality which may increase emotional and stress eating habits (Vidia et al., 2021). Emotional eating may relieve short-term distress, but can lead to excessive calorie intake, leading to obesity and chronic systemic inflammatory health conditions (Jacques et al., 2019: Barrea et al., 2021:de Queiroz et al., 2022) Comfort eating to cope with stress and mental health issues requires support and guidance to find alternative coping mechanisms such as CBT, meditation, exercise and balanced nutrition (Aninye et al., 2021). A study showed that educational awareness groups for men on menopause increased the support and empathy women experienced at home and positively impacted their perception of feeling socially supported (Namazi et al., 2019).

Social norms

Bourdieu’s Theory states health habits are strongly influenced by social norms of close friendships and family who become part of the individual’s identity and social class (Social capital) (Oncini & Guetto, 2017: Bourdieu, 2018: Spadine & Patterson, 2022) Family traditions, cultural and religious requirements may cause menopausal women to feel obligated to fulfil beliefs and rituals around food (Stanzel et al., 2021). The shared values and beliefs, around food behaviours generally mirror those around us, to feel accepted and comfortable (Iqbal et al., 2021) behaviour changes are difficult and isolating when different from the norm (Ragelien & Grønhøj, 2020). Raising awareness of how marketing targets women is also needed so that they do not fall prey to overconsumption of expensive vitamins and minerals or fall prey to misleading statements of healthy products which are in fact not (Hashemi et al., 2022: Ashwell et al., 2022). Pressure to fit in and attend gatherings and social / work events which encourage alcohol and food consumption not congruent to maintaining healthy habits require addressing (Kersey et al., (2022: Pegington et al., 2020). Furthermore, awareness and support may be needed for women who feel pressure to conform to body weight trends which may lead to disordered eating behaviours and nutritional deficiencies (Bremner et al., 2020). Social norms could be changed through campaigns empowering all women to make good nutritional choices and by encouraging community therapists, hairdressers, beauty salons to promote health education also (Michalak, 2020).

Cooking skills and Education

Some women lack cooking skills and nutrition awareness and may experience opportunity inequalities such as a lack of time, financial, equipment or resources (Marovelli, 2019). Skill gaps may include meal planning, shopping on a budget, knowledge of nutritional values and portion sizes (Ranjan et al., 2022). Menopause nutrition myths & trends are often confusing and conflicting, and many women are unsure of evidence-based recommendations, myth busting may be beneficial for this group of women who have been targeted (Van Royen et al., 2022). Support to access basic cookbooks from the library with recipes which are achievable for all budgets and skill sets using minimal equipment and expense may inspire more women (Alghamdi et al., 2023). Information on simple tips such as batch cooking to cut cooking fuel costs, shopping and reduce leftover waste, may empower women (LeBlanc-Morales, 2019: Biasin et al., 2021).

Research shows that women at this stage of life use a mixture of podcasts, social media, magazines, and documentaries for health information (Harper et al., 2022: Lupton & Maslen, 2019: Balls-Berry et al., 2018: Munn et al., 2022). One to one counselling, nutritional support and menopause specialist intervention has helped those who can access it financially (Dayaratna et al., 2021). The Divina McCall campaign with Dr Louise Newson increased demand for HRT by 30% with podcasts, social media posts and vlogging about the benefits of HRT, raising awareness of symptoms and of health language to guide women when visiting their G. P’s (Edwards et al., 2021).Using celebrities within campaigns and peer vicarious learning is a behaviour change method used often within public health (Hoffman et al., 2017: Klassen et al., 201: Sites, 2008).

Research shows that posters and infographics are better received when they have an official logo such as the NHS (Rowe & Ilic, 2009). The logo gives confidence that the literature is evidence based and safe to follow (Ilic & Rowe, 2013: Barlow et al., 2021). Confidence in the information is further reinforced when placed in surgeries, hospitals and social services (Mrudula & Latika, 2021). A slogan or tagline could be used to emphasise the message that good nutrition is important during menopause to reduce risk of noncommunicable diseases (Ling et al., 1992). The poster should include targeted messages for key nutrients important to health during this stage, and a call-to-action section where practical tips and meal suggestions supports the behaviour change (Snyder, 2007). The design should be based around the cohort chosen according to their age (40-60 years), background, and culture. The wording should be clear, concise, and easy to read (Naparin & Saad, 2017). Pictures can enhance key messages (Houts et al., 2006). Mc Sween-Cadieux et al., 2021).

The message should stick to the benefits of good nutrition during menopause and include up to date evidence based key nutrients required (Burchell et al., 2013). Visual hierarchy should be used to draw attention to key messages, using larger fonts (Spicer & Coleman, 2022). The message Colour choices known to maximize effectiveness of a menopause have a significant impact on the perception of the message delivered such as green is linked to growth, balance, nature and signifies vitality and renewal, blue is associated with calmness, serenity and trust, orange is warm and is thought to promote care, motivation and enthusiasm Pink is feminine and associated with compassion and nurturing and Purple is used in healing circles as a colour to promote introspection and self-discovery and creativity (Khattak et al., 2018: Heru, 2005: Cerrato, 2012 : Singh & Srivastava, 2011). Visuals such as Mediterranean diets or daily recommended intake charts as well as practical tips and recipe ideas can support and enhance literature but should be in keeping with health and wellbeing colour schemes (Gemayel, 2018: Aslam, 2006). The overall aim would be to empower women to make healthy food choices which enhance their health longevity and reduce challenging menopausal symptoms and future risks of osteoporosis and non-communicable diseases (Hickey et al., 2022).

References

Adler, N. E., & Ostrove, J. M. (1999). Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don't. Annals of the New York academy of Sciences, 896(1), 3-15.

Alghamdi, M. M., Burrows, T., Barclay, B., Baines, S., & Chojenta, C. (2023). Culinary Nutrition Education Programs in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 1-17.

Aninye, I. O., Laitner, M. H., & Chinnappan, S. (2021). Menopause preparedness: perspectives for patient, provider, and policymaker consideration. Menopause (New York, NY), 28(10), 1186.

Artiss, J. D., & Zak, B. (2000). Measurement of cholesterol concentration. Handbook of Lipoprotein Testing. AACC Press, New York, 189-205.

Ashwell, M., Hickson, M., Stanner, S., Prentice, A., & Williams, C. M. (2022). Nature of the evidence base and strengths, challenges and recommendations in the area of nutrition and health claims: a Position Paper from the Academy of Nutrition Sciences. British Journal of Nutrition, 1-18.

Aslam, M. M. (2006). Are you selling the right colour? A cross‐cultural review of colour as a marketing cue. Journal of marketing communications, 12(1), 15-30.

Balls-Berry, J., Sinicrope, P., Soto, M. V., Brockman, T., Bock, M., & Patten, C. (2018). Linking podcasts with social media to promote community health and medical research: feasibility study. JMIR formative research, 2(2), e10025.

Barbosa-Silva, M. C. G. (2008). Subjective and objective nutritional assessment methods: what do they really assess?. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 11(3), 248-254.

Barker, M., Dombrowski, S. U., Colbourn, T., Fall, C. H., Kriznik, N. M., Lawrence, W. T., ... & Stephenson, J. (2018). Intervention strategies to improve nutrition and health behaviours before conception. The Lancet, 391(10132), 1853-1864.

Barlow, B., Webb, A., & Barlow, A. (2021). Maximizing the visual translation of medical information: A narrative review of the role of infographics in clinical pharmacy practice, education, and research. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, 4(2), 257-266.

Barrea, L., Pugliese, G., Laudisio, D., Savastano, S., Colao, A., & Muscogiuri, G. (2021). Does mediterranean diet could have a role on age at menopause and in the management of vasomotor menopausal symptoms? The viewpoint of the endocrinological nutritionist. Current Opinion in Food Science, 39, 171-181.

Biasini, B., Rosi, A., Giopp, F., Turgut, R., Scazzina, F., & Menozzi, D. (2021). Understanding, promoting and predicting sustainable diets: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 111, 191-207.

Bremner, J. D., Moazzami, K., Wittbrodt, M. T., Nye, J. A., Lima, B. B., Gillespie, C. F., ... & Vaccarino, V. (2020). Diet, stress and mental health. Nutrients, 12(8), 2428.

Burchell, K., Rettie, R., & Patel, K. (2013). Marketing social norms: social marketing and the ‘social norm approach’. Journal of Consumer behaviour, 12(1), 1-9.

Burns, A., Dannecker, E., & Austin, M. J. (2019). Revisiting the biological perspective in the use of biopsychosocial assessments in social work. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(2), 177-194.

Butler, T. G., Gullotta, M., & Greenberg, D. (2022). Reliability of prisoners’ survey responses: comparison of self-reported health and biomedical data from an australian prisoner cohort. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1-6.

Cerrato, H. (2012). The meaning of colors. The graphic designer.

Chen, L. R., & Chen, K. H. (2021). Utilization of Isoflavones in Soybeans for Women with Menopausal Syndrome: An Overview. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(6), 3212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22063212

Christie, J., & ND, C. (2023). How to Build a Personalized Nutrition Plan for Your Perimenopausal Patients. Nutrition.

Cronin, C., Hungerford, C., & Wilson, R. L. (2021). Using digital health technologies to manage the psychosocial symptoms of menopause in the workplace: a narrative literature review. Issues in mental health nursing, 42(6), 541-548.

Dao, M. C., Subar, A. F., Warthon-Medina, M., Cade, J. E., Burrows, T., Golley, R. K., ... & Holmes, B. A. (2019). Dietary assessment toolkits: an overview. Public health nutrition, 22(3), 404-418.

Dayaratna, S., Sifri, R., Jackson, R., Powell, R., Sherif, K., DiCarlo, M., ... & Myers, R. (2021). Preparing women experiencing symptoms of menopause for shared decision making about treatment. Menopause, 28(9), 1060-1066.

De Franciscis, P., Colacurci, N., Riemma, G., Conte, A., Pittana, E., Guida, M., & Schiattarella, A. (2019). A nutraceutical approach to menopausal complaints. Medicina, 55(9), 544.

de Queiroz, F. L. N., Raposo, A., Han, H., Nader, M., Ariza-Montes, A., & Zandonadi, R. P. (2022). Eating competence, food consumption and health outcomes: An overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4484.

Dehghan, M., & Merchant, A. T. (2008). Is bioelectrical impedance accurate for use in large epidemiological studies?. Nutrition journal, 7(1), 1-7.

Devarshi, P. P., Legette, L. L., Grant, R. W., & Mitmesser, S. H. (2021). Total estimated usual nutrient intake and nutrient status biomarkers in women of childbearing age and women of menopausal age. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 113(4), 1042-1052.

Diolintzi, A., Panagiotakos, D. B., & Sidossis, L. S. (2019). From Mediterranean diet to Mediterranean lifestyle: a narrative review. Public health nutrition, 22(14), 2703-2713.

Dixon, B. N., Ugwoaba, U. A., Brockmann, A. N., & Ross, K. M. (2021). Associations between the built environment and dietary intake, physical activity, and obesity: A scoping review of reviews. Obesity Reviews, 22(4), e13171.

Dubey, P., Thakur, V., & Chattopadhyay, M. (2020). Role of minerals and trace elements in diabetes and insulin resistance. Nutrients, 12(6), 1864.

Forman, M. R., Mangini, L. D., Thelus-Jean, R., & Hayward, M. D. (2013). Life-course origins of the ages at menarche and menopause. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 1-21.

Frankenfeld, C. L., Poudrier, J. K., Waters, N. M., Gillevet, P. M., & Xu, Y. (2012). Dietary intake measured from a self-administered, online 24-hour recall system compared with 4-day diet records in an adult US population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(10), 1642-1647.

Freeman, E. W., & Sherif, K. (2007). Prevalence of hot flushes and night sweats around the world: a systematic review. Climacteric, 10(3), 197-214.

Gadgil, N. D., & Kulkarni, A. A. (2019). An Understanding and Comprehensive Approach Towards Perimenopausal Stress–A Review.

Ghazi, L., Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Abbasi Fard, S., Sadeghi, M., Shahidi, G. A., & Lökk, J. (2015). Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) is rather a reliable and valid instrument to assess nutritional status in Iranian healthy adults and elderly with a chronic disease. Ecology of food and nutrition, 54(4), 342-357.

Guasch‐Ferré, M., & Willett, W. C. (2021). The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. Journal of internal medicine, 290(3), 549-566.

Gupta, A., Osadchiy, V., & Mayer, E. A. (2020). Brain–gut–microbiome interactions in obesity and food addiction. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 17(11), 655-672.

Harper, J. C., Phillips, S., Biswakarma, R., Yasmin, E., Saridogan, E., Radhakrishnan, S., ... & Talaulikar, V. (2022). An online survey of perimenopausal women to determine their attitudes and knowledge of the menopause. Women's Health, 18, 17455057221106890.

Harrison, G. G., Galal, O. M., Ibrahim, N., Khorshid, A., Stormer, A., Leslie, J., & Saleh, N. T. (2000). Underreporting of food intake by dietary recall is not universal: a comparison of data from Egyptian and American women. The Journal of nutrition, 130(8), 2049-2054.

Hashemi, H., Ghareghani, S., Nasimi, N., Shahbazi, M., Derakhshan, Z., & Sarkodie, S. A. (2022). Health Consequences of Overexposure to Disinfectants and Self-Medication against SARS-CoV-2: A Cautionary Tale Review. Sustainability, 14(20), 13614.

Hastings, G., MacFadyen, L., & Anderson, S. (2000). Whose behavior is it anyway? The broader potential of social marketing. Social Marketing Quarterly, 6(2), 46-58.

Hebert, J. R., Ockene, I. S., Hurley, T. G., Luippold, R., Well, A. D., & Harmatz, M. G. (1997). Development and testing of a seven-day dietary recall. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 50(8), 925-937.

Heru, A. M. (2005). Pink-collar medicine: Women and the future of medicine. Gender Issues, 22(1), 20-34.

Heyward, V. (2001). ASEP methods recommendation: body composition assessment. Journal of exercise physiology online, 4(4).

Hickey, M., Hunter, M. S., Santoro, N., & Ussher, J. (2022). Normalising menopause. bmj, 377.

Hickey, M., Hunter, M. S., Santoro, N., & Ussher, J. (2022). Normalising menopause. bmj, 377.

Hoffman, S. J., Mansoor, Y., Natt, N., Sritharan, L., Belluz, J., Caulfield, T., ... & Sharma, A. M. (2017). Celebrities’ impact on health-related knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and status outcomes: protocol for a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis. Systematic reviews, 6(1), 1-13.

Houts, P. S., Doak, C. C., Doak, L. G., & Loscalzo, M. J. (2006). The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient education and counseling, 61(2), 173-190.

Hunter, M. M., Huang, A. J., & Wallhagen, M. I. (2020). " I’m going to stay young": Belief in anti-aging efficacy of menopausal hormone therapy drives prolonged use despite medical risks. PloS one, 15(5), e0233703.

Iqbal, A. S. M., Jan, M. T., Muflih, B. K., & Jaswir, I. (2021). The role of prophetic food in the prevention and cure of chronic diseases: A review of literature. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 6(11), 366-375.

Jacques, A., Chaaya, N., Beecher, K., Ali, S. A., Belmer, A., & Bartlett, S. (2019). The impact of sugar consumption on stress driven, emotional and addictive behaviors. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 103, 178-199.

Jamil, A. S., Alalaf, S. K., Al-Tawil, N. G., & Al-Shawaf, T. (2015). A case–control observational study of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome among the four phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome based on Rotterdam criteria. Reproductive Health, 12(1), 1-9.

Jayasinghe, S., Faghy, M. A., & Hills, A. P. (2022). Social justice equity in healthy living medicine-An i Chopra, S., Sharma, K. A., Ranjan, P., Malhotra, A., Vikram, N. K., & Kumari, A. (2019). Weight management module for perimenopausal women: A practical guide for gynecologists. Journal of mid-life health, 10(4), 165. nternational perspective. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases.

Kersey, K., Lyons, A. C., & Hutton, F. (2022). Alcohol and drinking within the lives of midlife women: A meta-study systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 99, 103453.

Khandelwal, S. (2020). Obesity in midlife: lifestyle and dietary strategies. Climacteric, 23(2), 140-147.

Khattak, D.S.R, Ali, Haider, Khan, Yasir, & Shah, M. (2018). Color psychology in marketing. Journal of Business & Tourism, 4(1), 183-190.

Klesges, R. C., Eck, L. H., & Ray, J. W. (1995). Who underreports dietary intake in a dietary recall? Evidence from the Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 63(3), 438.

Ko, S. H., & Kim, H. S. (2020). Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients, 12(1), 202.

Ko, S. H., & Kim, H. S. (2020). Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients, 12(1), 202.

Kostecka, M. (2014). The role of healthy diet in the prevention of osteoporosis in perimenopausal period. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 30(4), 763.

Lafrenière, J., Laramée, C., Robitaille, J., Lamarche, B., & Lemieux, S. (2018). Assessing the relative validity of a new, web-based, self-administered 24 h dietary recall in a French-Canadian population. Public health nutrition, 21(15), 2744-2752.

LeBlanc-Morales, N. (2019). Culinary medicine: patient education for therapeutic lifestyle changes. Critical Care Nursing Clinics, 31(1), 109-123.

Lee, A. R. Y. B., Tariq, A., Lau, G., Tok, N. W. K., Tam, W. W. S., & Ho, C. S. H. (2022). Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol, and its effects on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 14(3), 656.

Lee, R. D. (2010). Nutritional assessment/Robert D. Robert, David C. Nieman. New York [etc.]: McGraw-Hill, 2003..

Li, D., Tong, Y., & Li, Y. (2020). Associations between dietary oleic acid and linoleic acid and depressive symptoms in perimenopausal women: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Nutrition, 71, 110602.

Lupton, D., & Maslen, S. (2019). How women use digital technologies for health: qualitative interview and focus group study. Journal of medical Internet research, 21(1), e11481.

Maghalian, M., Hasanzadeh, R., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2022). The effect of oral vitamin E and omega-3 alone and in combination on menopausal hot flushes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Post Reproductive Health, 28(2), 93-106.

Maghalian, M., Hasanzadeh, R., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2022). The effect of oral vitamin E and omega-3 alone and in combination on menopausal hot flushes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Post Reproductive Health, 28(2), 93-106.

Maltais, M. L., Desroches, J., & Dionne, I. J. (2009). Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact, 9(4), 186-197.

Maresz, K. (2015). Proper calcium use: vitamin K2 as a promoter of bone and cardiovascular health. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician's Journal, 14(1), 34.

Marovelli, B. (2019). Cooking and eating together in London: Food sharing initiatives as collective spaces of encounter. Geoforum, 99, 190-201.

Mc Sween-Cadieux, E., Chabot, C., Fillol, A., Saha, T., & Dagenais, C. (2021). Use of infographics as a health-related knowledge translation tool: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ open, 11(6), e046117.

McNamara, M., Batur, P., & DeSapri, K. T. (2015). Perimenopause. Annals of internal medicine, 162(3), ITC1-ITC16.

Michalak, M. (2020). The role of a cosmetologist in the area of health promotion and health education: A systematic review. Health Promotion Perspectives, 10(4), 338-348.

Milart, P., Woźniakowska, E., & Wrona, W. (2018). Selected vitamins and quality of life in menopausal women. Przeglad menopauzalny= Menopause review, 17(4), 175.

Mohammady, M., Janani, L., Jahanfar, S., & Mousavi, M. S. (2018). Effect of omega-3 supplements on vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 228, 295-302.

Mohapatra, S., Iqbal, Z., Ahmad, S., Kohli, K., Farooq, U., Padhi, S., ... & Panda, A. K. (2020). Menopausal remediation and quality of life (QoL) improvement: insights and perspectives. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders), 20(10), 1624-1636.

Munn, C., Vaughan, L., Talaulikar, V., Davies, M. C., & Harper, J. C. (2022). Menopause knowledge and education in women under 40: Results from an online survey. Women's Health, 18, 17455057221139660.

Namazi, M., Sadeghi, R., & Behboodi Moghadam, Z. (2019). Social determinants of health in menopause: an integrative review. International Journal of Women's Health, 637-647.

Naparin, H., & Saad, A. B. (2017). Infographics in education: Review on infographics design. The International Journal of Multimedia & Its Applications (IJMA), 9(4), 5.

Nemati, A., & Baghi, A. N. (2008). Assessment of nutritional status in post menopausal VVomen of Ardebil, Iran. Journal of Biological Sciences, 8(1), 196-200.

Nordin, B. C., Need, A. G., Morris, H. A., O'Loughlin, P. D., & Horowitz, M. (2004). Effect of age on calcium absorption in postmenopausal women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 80(4), 998-1002.

Plank, L. D. (2005). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and body composition. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 8(3), 305-309.

Ragelienė, T., & Grønhøj, A. (2020). The influence of peers′ and siblings′ on children’s and adolescents′ healthy eating behavior. A systematic literature review. Appetite, 148, 104592.

Reber, E., Gomes, F., Vasiloglou, M. F., Schuetz, P., & Stanga, Z. (2019). Nutritional risk screening and assessment. Journal of clinical medicine, 8(7), 1065.

Rizzoli, R., Bischoff-Ferrari, H., Dawson-Hughes, B., & Weaver, C. (2014). Nutrition and bone health in women after the menopause. Women’s Health, 10(6), 599-608.

Rowe, N., & Ilic, D. (2009). What impact do posters have on academic knowledge transfer? A pilot survey on author attitudes and experiences. BMC medical education, 9, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-71

Salminen, H., Sääf, M., Johansson, S. E., Ringertz, H., & Strender, L. E. (2006). Nutritional status, as determined by the Mini-Nutritional Assessment, and osteoporosis: a cross-sectional study of an elderly female population. European journal of clinical nutrition, 60(4), 486-493.

Sauberlich, H. E. (2018). Laboratory tests for the assessment of nutritional status. Routledge.

Sauberlich, H. E. (2018). Laboratory tests for the assessment of nutritional status. Routledge.

Sayón-Orea, C., Santiago, S., Cuervo, M., Martínez-González, M. A., Garcia, A., & Martínez, J. A. (2015). Adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern and menopausal symptoms in relation to overweight/obesity in Spanish perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause, 22(7), 750-757.

Singh, N., & Srivastava, S. K. (2011). Impact of colors on the psychology of marketing—A Comprehensive over view. Management and Labour Studies, 36(2), 199-209.

Sites, C. K. (2008). Bioidentical hormones for menopausal therapy. Women’s Health, 4(2), 163-171.

Spadine, M., & Patterson, M. S. (2022). Social influence on fad diet use: a systematic literature review. Nutrition and Health, 28(3), 369-388.

Spicer, J. O., & Coleman, C. G. (2022). Creating effective infographics and visual abstracts to disseminate research and facilitate medical education on social media. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 74(Supplement_3), e14-e22.

Steenson, S., & Buttriss, J. L. (2021). Healthier and more sustainable diets: what changes are needed in high‐income countries?. Nutrition Bulletin, 46(3), 279-309.

Stockton, K. A., Mengersen, K., Paratz, J. D., Kandiah, D., & Bennell, K. L. (2011). Effect of vitamin D supplementation on muscle strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis international, 22, 859-871.

Stute, P., & Lozza-Fiacco, S. (2022). Strategies to cope with stress and anxiety during the menopausal transition. Maturitas.

Su, Y., & Zhang, D. (2022). Management of menopausal physiological symptoms. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, 14, 163-170.

Suarez-Almazor, M. E. (2011). Changing health behaviors with social marketing. Osteoporosis International, 22, 461-463.

Sunyecz, J. A. (2008). The use of calcium and vitamin D in the management of osteoporosis. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 4(4), 827-836.

Svendsen, O. L., Hassager, C., & Christiansen, C. (1993). Effect of an energy-restrictive diet, with or without exercise, on lean tissue mass, resting metabolic rate, cardiovascular risk factors, and bone in overweight postmenopausal women. The American journal of medicine, 95(2), 131-140.

These include phytoestrogen plants or isoflavones, antioxidants, dietary supplements

Thomas, A. J., Mitchell, E. S., & Woods, N. F. (2018). The challenges of midlife women: themes from the Seattle midlife women’s health study. Women's Midlife Health, 4(1), 1-10.

Thomson, C. A., Stanaway, J. D., Neuhouser, M. L., Snetselaar, L. G., Stefanick, M. L., Arendell, L., & Chen, Z. (2011). Nutrient intake and anemia risk in the women's health initiative observational study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(4), 532-541.

Toklu, H. İ. L. A. L., & Nogay, N. H. (2018). Effects of dietary habits and sedentary lifestyle on breast cancer among women attending the oncology day treatment center at a state university in Turkey. Nigerian journal of clinical practice, 21(12), 1576-1584.

Uehara, M., Wada-Hiraike, O., Hirano, M., Koga, K., Yoshimura, N., Tanaka, S., & Osuga, Y. (2022). Relationship between bone mineral density and ovarian function and thyroid function in perimenopausal women with endometriosis: a prospective study. BMC Women's Health, 22(1), 1-9.

Van Pelt, R. E., Evans, E. M., Schechtman, K. B., Ehsani, A. A., & Kohrt, W. M. (2001). Waist circumference vs body mass index for prediction of disease risk in postmenopausal women. International journal of obesity, 25(8), 1183-1188.

Van Royen, K., Pabian, S., Poels, K., & De Backer, C. (2022). Around the same table: Uniting stakeholders of food-related communication. Appetite, 105998.

van Wijngaarden, J. P., Dhonukshe-Rutten, R. A., van Schoor, N. M., van der Velde, N., Swart, K., Enneman, A. W., ... & de Groot, L. C. (2011). Rationale and design of the B-PROOF study, a randomized controlled trial on the effect of supplemental intake of vitamin B12and folic acid on fracture incidence. BMC geriatrics, 11(1), 1-11.

Vidia, R. A., Ratrikaningtyas, P. D., & Rachman, I. T. (2021). Factors affecting sexual life of menopausal women: scoping review.. European Journal of Public Health Studies, 4(2).

Witte, K., Maibach, E., & Parrot, R. L. (1995). Using the persuasive health message framework to generate effective campaign messages. Designing health messages, 145-164.

Woods, N. F., Coslov, N., & Richardson, M. K. (2022). Perimenopause meets life: observations from the Women Living Better Survey. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 29(12), 1388–1398. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002072

World Health Organization. (1994). Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group [meeting held in Rome from 22 to 25 June 1992]. World Health Organization.

Woźniak-Holecka, J., & Sobczyk, K. (2014). Nutritional education in the primary prevention of osteoporosis in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Menopause Review/Przegląd Menopauzalny, 13(1), 56-63.

Yazdkhasti, M., Simbar, M., & Abdi, F. (2015). Empowerment and coping strategies in menopause women: a review. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(3).

Yelland, S., Steenson, S., Creedon, A., & Stanner, S. (2023). The role of diet in managing menopausal symptoms: A narrative review. Nutrition Bulletin.