Behaviour Change Case Study (fictional).

Clare’s perceived barriers to exercise are largely around self-belief psychologically and physically. I noticed that Clare often feels sad and scared, she lacks confidence to engage in daily living activities without encouragement and doesn’t appear to trust her own judgements, capabilities, and skills to navigate the world without support, she does appear to have good self-awareness and understands how behaviours impact close relationships and she possesses the motivation and time implement changes.

Clare appears to lack belief that exercise will work for her and feels ambivalent and is therefore in the contemplating stage of the TTM (Zimmerman et al.,2000). She stated she has social phobias of group settings, and feels she needs high levels of support to achieve change, which highlighted low self-belief (Dobson et al.,2016) in her capabilities psychologically and physically linking to self-efficacy (SE) which is the largest theme throughout the case study and a common predictor of exercise adherence (Bandura et al.,1999: Husebo et al.,2015). Enhancing SE will impact positively on the other barriers; High SE predicts persistence and effort expenditure, therefore improved SE will have a favourable and supportive influence on other barriers (Alharbi et al.,2017).

in 1977; Albert Bandura published his paper “SE: toward a unifying theory of Behaviour Change (BC)”, it has since been used within healthcare of all forms as a construct for many BC models (Maddux, 2002, P201). SE is not a skill but a belief or a perceived capability which is sub-conscious and autonomic in nature, it is built over time from our life experiences (Pettit & Karageorghis.,2020). Bandura, (1981) believed that parental responses and early environments shaped the individual’s SE and children who did not have a secure attachment in early childhood, who experienced a lack of parental guidance, positive role modelling and encouragement developed low SE leading to avoidance of goal attainment due to high uncomfortable arousal states, distraction by their own thoughts, a lack of motivation and negativity toward new tasks (Schunk & Pajares, 2009, P41).

SE is evidenced to be fundamental for exercise adherence, according to Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura,1989: Plotnikoff et al.,2013). Bandura (1977) suggested that people avoid activities they feel exceeds their capabilities or coping mechanisms and seek experiences they feel they can execute well. Improved SE and outcome expectations is thought to boost the likelihood of adherence to an exercise programme (Shaughnessy et al.,2006: Resnick et al.,2000). Many contemporary studies have highlighted exercise referral schemes need to address barriers including SE for successful long-term adherence (Williams et al.,2007; Cleland et al.,2019: Eynon et al.,2019: McAuley & Blissmer,2000: McAuley et al.,2006).

SE is the underlying construct within the Social cognitive model (Bandura,1989; Schunk,1989) which is highlighted on the taxonomy BC mapping interventions; evidenced to support Clare’s barriers to exercise. The Theory has four main concepts: Mastery of new experiences through practice of incremental small goals giving a sense of achievement at each stage, modelling, and observation, allowing Clare to experience positive physiological states in the form of Serotonin and Oxytocin; producing feelings of safety and eliciting the motivation to continue with further goals (Stone,2018). Some have argued that SE reflects motivation; rather than being a factor that determines motivation (Williams & Rhodes,2016).

Clare appears to feel ambivalent about physical activity according to the taxonomy she would benefit from the health belief model (HBM), created in the 1950’s for public health screening (Strecher & Rosenstock,1997) and since to predict exercise and eating behaviours (Champion & Skinner, 2008). The model would be useful to identify Clare’s beliefs around Perceived severity/seriousness and the impact on relationships if she chooses not to change the behaviour (Guidry et al.,2021). Using the model to identify whether she perceives she has control of her behaviour or believes the benefits (outcomes) outweigh the sacrifice, identifying the cost and physical/psychological barriers such as social phobias and financial constraints, and mobilizing support in the form of cues to action such as reminders, appointment commitments and practised SE (Volkmer et al.,2021). Critiques have highlighted the HBM is a threat-based behaviour prediction, and therefore not a reliable predictor due to humans not being under constant threat (Di Giuseppe et al.,2022).

Theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is an extension of The Theory of Reasoned Action; evidenced to be effective in predicting behaviour through investigation of the individuals conscious and subconscious intentions to change behaviour. Beliefs around whether the behaviour (sedentary) is harmful, assessing subjective norms e.g., whether Clare’s boyfriend and family wish Clare to be sedentary, perceived behavioural control e.g., being sedentary is easy for Clare, behavioural intention e.g., Clare intends to be sedentary (Mesters et al.,2014: Ryan & Carr,2010). Criticisms emphasised the need to include a wider range of intentions within the constructs, to enhance its viability (Sniehotta et al.,2014).

Co-creating strategies to increase Clare’s beliefs around capabilities and self-belief would start with listing all barriers, before scoring the behaviours in terms of both importance and the biggest impact on likelihood of BC. Ensuring Clare deals with a few behaviours at one time and incrementally builds upon them (Michie, 2008: Ojo et al.,2019). Clare is likely to prefer 121 works initially, support must include an empathetic and patient approach and goals (Allen,2014: Valente,2015)).

Michie and colleagues put together a taxonomy of BC models and theories which are evidence based; encouraging BC therapists to follow the step-by-step process for best results (Michie et al.,2013: Abraham & Michie,2008). Adopting the TDF, Com-b and Taxonomy intervention mapping enhances consistency across the field (Cane et al.,2012), ensuring safety for Clare and enabling clinical based measurement and reflection Michie et al.,2011).

Clare’s fears of exertion negatively impacting her heart condition and depression has been a barrier to exercising, this is common amongst individuals with chronic conditions (Jerant et al.,2005). She doesn’t yet have up-to-date information and experience of the benefits of exercise (McInnis et al.,2003). The Social Cognitive model (Parks et al.,2007: Aaltonen et al.,2014: Resnick et al.,2008), The Self-regulation model (SRM) and Modelling theory (Kelder et al.,2015) are evidenced to support this. The SRM is a framework which can include attention and emotion control, goal setting, planning, monitoring, and metacognitive knowledge, mapping the interplay between coping and self-regulation in times of stress, outside negative influences, and past triggers (Detweiler-Bedell et al.,2008: Pedersen & Saltin,2015).

Depression has many symptoms including poor concentration, fatigue, sleep deprivation which may make Clare feel that the exerted effort is not worth it. Under regulation may be due to Clare's difficulty in managing a range of maladaptive cognitions, hence it is important to agree on the most important aspect to manage in a way which does not conflict with other conditions (Detweiler-Bedell et al.,2008). Commitment to adopt and maintain regular exercise in place of health-damaging behaviours is likely to improve long-term BC, if Clare successfully foresees barriers which may arise when she intends to exercise and executes consistent strong, intrinsic, healthy behaviours which override emotional, impulsive automatic behaviours that are familiar (Schwarzer, 2011: Stadler et al.,2009). Clare may benefit from a phone exercise app, which provides self- monitoring, normative feedback, action planning and identity change. The app may also help Clare feel more supported and able to reduce the high level of support required (Vinnikova et al.,2020).

Clare’s financial barrier sits within the TDF as an environmental lack of opportunity (Cane et al.,2012), a common barrier for people from disadvantaged backgrounds who are more likely to have poorer health, less access to facilities, green spaces and support (Kirkham et al.,2018).), further exacerbated by the COVID pandemic (Fegert et al.,2020: Cauwenberg et al.,2018). Opportunity intervention would be to mobilise social support. Clare would benefit from an exercise prescription specialist or social prescriber who communicates with empathy, trust, and care to reduce financial and physical barriers (Valente,2015: Martín-Borràs et al.,2018)

Clare currently holds the belief that her heart condition and depression are barriers to exercising. Establishing beliefs about capabilities on the TDF, before working with Clare to establish what knowledge gaps she feels are advantageous to learn, and providing environmental information on facilities, myth busting and challenging beliefs around gym perceptions ((Glegg & Levac, 2018: Nikolajsen et al.,2021). Clare would benefit from vicarious observation: Identifying groups as positive role models who have overcome health adversity, who are relatable (Borek & Abraham,2018). A commitment to training in person and homebased exercise guidance between sessions, utilising video call sessions and diary records for self-reflection / self-regulation (Crane et al.,2018). Clare could utilise the knowledge alongside repeated supported exposure to overcome social phobias and master the physical activity goals (Garcia,2017).

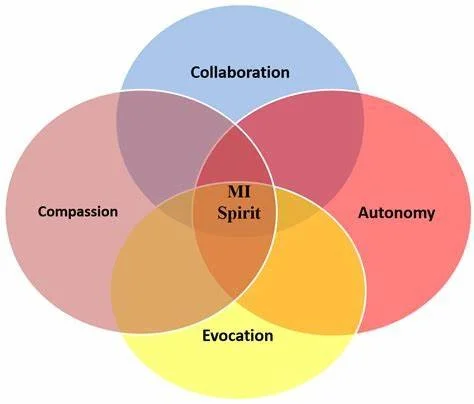

Clare has the motivation to set goals, motivation is a key construct of the Com-b model which predicts likelihood of behaviour change, it is evidenced that without motivation BC is unlikely to succeed (Weiner,2009). Whilst SE is an important construct to initiate change, motivation is needed to maintain adherence (Slovinec et al.,2014). Motivational interviewing is a client centered approach to empower individuals to co-create a plan of action to overcome behaviours which are detrimental to their quality of life (QOL) (Westar,2004: Budhwani et al.,2021). Motivation is evidenced to support exercise adherence and links to Transtheoretical model (TTM), Stages of change model, and motivational theories such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Turner & Reed,2022).

The TTM, Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983 consists of 5 stages of change and may be used to identify the current stage, Clare’s beliefs, and behaviours (consciousness raising), to enable the best strategy to move forward (Velicer et al.,1999: Merz & Steinherr,2021). Where the HBM was designed for health promotion on a population level, the TTM was designed specifically to change individual behaviour; historically is has been used for smoking intervention, however more recently it has been used for exercise BC (Marshall & Biddle,2001) Criticisms of the model include that it neglects impulse / automatic decision-making (West,2006), and that there are no stages of change, only transient, fluctuating cycles of change; it also does not support how to change (West, R. (2005). There are many studies highlighting successful uses for the model (Wagner et al.,2004: Petrocelli,2002: Taylor et al.,2006).

Clare has the incentive to improve her relationship (a goal) and studies have shown goal incentives; if relatable and achievable to be a strong factor for adherence (Davey et al.,2015). linked models for BC commonly used are: Social Cognitive theory, Goal-setting Theory, and self-determination theory (SDT) and the self-determination continuum.

It is accepted within the PA community that adherence to exercise has a 50% drop out within six months due to reported changes in motivation, a lack of improvement, boredom, and a lack of support / accountability (Wilson & Brookfield,2009). BC practitioners could use the (SDT) by Deci and Ryan,1985, with Clare to discover her intrinsic motivations, activities which bring joy and feel effortless, whilst avoiding the associated guilt and resentful feelings associated with extrinsic goals (Deci & Ryan,2008). The goals require relatability, autonomy and must evoke positive feelings to be sustainable and drive increased effort (Ryan & Patrick,2009: Chatzisarantis,2006). Positive psychology, empowerment and goal setting is preferred by six out of 10 people in psychotherapy. Giving Clare full control over her goals ensures cohesion and agreed focus for support worker and Clare (Cooper& Law,2018. Pg 7-9). There is a large bank of studies showing the effectiveness of the SDT for exercise which could support adherence (Clare Wilson et al.,2008).

Goal Theory intentions highlights the gap between positive intentions to adhere to a goal, behaviour, and failure to perform (Weinstein,1993). By harnessing the SDT Clare can co-create Intrinsic health goals which are relatable and autonomous (Berking et al.,2005: Sheldon & Houser Marko,2001: Ryan & Deci 2000). Where would she like to exercise? what activities bring joy? The Specificity of a goal is associated to simplicity and tangibility, avoiding abstract, vague and complex goals (Locke & Latham,2002: Sheeran & Webb,2012) e.g. I want to be fit and healthy would be vague, as apposed to I would like to hike two times a week. Temporal extension refers to focusing on proximal therapeutic goals as apposed to long-term life goals. Proximal goals supports likelihood of success and allows incremental successes to build supporting SE (Hanley et al.,2015: Macrill,2001). Clare will be focused on Volitional goals, unconsciously it is likely that she will have other complex goals at play, such as her need to build trust with the support worker, which would likely test / evoke the support worker to ensure they care and are trustworthy. It is therefore vital to remain open, accepting and present whilst Clare attains the unconscious goals (Marine et al.,2012: Moskowitz & Grant,2009): Bargh & Ferguson,2000). Applying person centered goal attainment using SDT is evidenced to support this (Flannery et al.,2018: Gould et al.,2017).

Motivational interviewing requires a humanistic approach to Co-create goals which would allow Clare to practice problem-solving and therefore build self-trust and resilience, overtime lessening her reliance on high levels of support (Padesky & Mooney,2012) and attain emotional stability (Rupani et al., 2014). Establishing morals and values, evoking happy feelings by not viewing the goal as problematic and identifying the positives e.g., Clare has the motivation and time to implement goals (Carey et al.,2019), and finally goals need Planning, mastery and feedback (Pappies,2016). Clare would benefit from incrementally building on outdoor exercise, initiation of small groups of likeminded people overtime, supporting Clare through the exposure of sporting facilities to build capability and SE (Resnick et al.,2008 Martin & Murtagh,2015).

References

Aaltonen, S., Rottensteiner, M., Kaprio, J., & Kujala, U. M. (2014). Motives for physical activity among active and inactive persons in their mid‐30s. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 24(4), 727-735

Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in interventions. Health psychology, 27(3), 379.

Alharbi, M., Gallagher, R., Neubeck, L., Bauman, A., Prebill, G., Kirkness, A., & Randall, S. (2017). Exercise barriers and the relationship to self-efficacy for exercise over 12 months of a lifestyle-change program for people with heart disease and/or diabetes. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 16(4), 309-317.

Allen, R. (2014). The role of the social worker in adult mental health services. London: The College of Social Work.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.

Bandura, A. (1981). Self-referent thought: A developmental analysis of self-efficacy. Social cognitive development: Frontiers and possible futures, 200(1), 239.

Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control.

Bandura, A., Valentine, E. R., Nesdale, A. R., Farr, R., Goodnow, J. J., Lloyd, B., & Duveen, G. (1989). Social cognition.

Berking, M., Grosse Holtforth, M., Jacobi, C., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2005). Empirically based guidelines for goal-finding procedures in psychotherapy: Are some goals easier to attain than others? Psychotherapy Research, 15(3), 316-324.

Borek, A. J., & Abraham, C. (2018). How do small groups promote behaviour change? An integrative conceptual review of explanatory mechanisms. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 10(1), 30-61.

Budhwani, H., Bulls, M., & Naar, S. (2021). Proof of concept for the FLEX intervention: Feasibility of home-based coaching to improve physical activity outcomes and viral load suppression among African American Youth Living with HIV. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 20, 2325958220986264.

Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domain’s framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation science, 7(1), 1-17.

Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains’ framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation science, 7(1), 1-17.

Carey, R. N., Connell, L. E., Johnston, M., Rothman, A. J., De Bruin, M., Kelly, M. P., & Michie, S. (2019). behaviour change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 53(8), 693-707.

Champion, V. L., & Skinner, C. S. (2008). The health belief model. Health behaviour and health education: Theory, research, and practice, 4, 45-65.

Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2006). Understanding motivation in sport: An experimental test of achievement goal and self-determination theories. European Journal of Sport Science, 6(1), 51.

Cleland, V., Nash, M., Sharman, M. J., & Claflin, S. (2019). Exploring the health-promoting potential of the “parkrun” phenomenon: what factors are associated with higher levels of participation? American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(1), 13-23.

Cooper, M., & Law, D. (Eds.). (2018). Working with goals in psychotherapy and counselling. Oxford University Press.

Crane, D., Garnett, C., Michie, S., West, R., & Brown, J. (2018). A smartphone app to reduce excessive alcohol consumption: Identifying the effectiveness of intervention components in a factorial randomised control trial. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-11.

Davey, P., Peden, C., Charani, E., Marwick, C., & Michie, S. (2015). Time for action—improving the design and reporting of behaviour change interventions for antimicrobial stewardship in hospitals: early findings from a systematic review. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 45(3), 203-212.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182-185.

Detweiler-Bedell, J. B., Friedman, M. A., Leventhal, H., Miller, I. W., & Leventhal, E. A. (2008). Integrating co-morbid depression and chronic physical disease management: identifying and resolving failures in self-regulation. Clinical psychology review, 28(8), 1426-1446.

Detweiler-Bedell, J. B., Friedman, M. A., Leventhal, H., Miller, I. W., & Leventhal, E. A. (2008). Integrating co-morbid depression and chronic physical disease management: identifying and resolving failures in self-regulation. Clinical psychology review, 28(8), 1426-1446.

Di Giuseppe, K., West, R., Furlong, T., Ussher, G., Santos, M., & Skipper, K. (2022). Advocating for community-based behavioural approaches within the combination HIV prevention framework: A critical literature review.

Dobson, F., Bennell, K. L., French, S. D., Nicolson, P. J., Klaasman, B. R. N., Holden, M. A., ... & Hinman, R. S. (2016). Barriers and Facilitators to Exercise Participation in People with Hip and/or Knee Osteoarthritis. American Journal of Physical, 894(9115/16), 9505-0372.

Eynon, M., Foad, J., Downey, J., Bowmer, Y., & Mills, H. (2019). Assessing the psychosocial factors associated with adherence to exercise referral schemes: A systematic review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 29(5), 638-650.

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 14(1), 1-11.

Flannery, C., McHugh, S., Anaba, A. E., Clifford, E., O’Riordan, M., Kenny, L. C., ... & Byrne, M. (2018). Enablers and barriers to physical activity in overweight and obese pregnant women: an analysis informed by the theoretical domain’s framework and COM-B model. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 18(1), 1-13.

Fox, J., & Bailenson, J. N. (2009). Virtual Self-Modelling: The Effects of Vicarious Reinforcement and Identification on Exercise Behaviours. Media Psychology, 12, 1-25.

Garcia, R. (2017). Neurobiology of fear and specific phobias. Learning & Memory, 24(9), 462-471.

Glegg, S. M. N., & Levac, D. E. (2018). Barriers, facilitators, and interventions to support virtual reality implementation in rehabilitation: a scoping review. PM&R, 10(11), 1237-1251.

Gould, G. S., Bar-Zeev, Y., Bovill, M., Atkins, L., Gruppetta, M., Clarke, M. J., & Bonevski, B. (2017). Designing an implementation intervention with the Behaviour Change Wheel for health provider smoking cessation care for Australian Indigenous pregnant women. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1-14.

Guidry, J. P., Laestadian, L. I., Vraga, E. K., Miller, C. A., Perrin, P. B., Burton, C. W., ... & Carlyle, K. E. (2021). Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. American journal of infection control, 49(2), 137-142.

Hanley, T., Sefi, A., & Ersahin, Z. (2016). From goals to tasks and methods. The handbook of pluralistic counselling and psychotherapy, 28-41.

Huang, G., & Ren, Y. (2020). Linking technological functions of fitness mobile apps with continuance usage among Chinese users: Moderating role of exercise self-efficacy. Computers in Human Behaviour, 103, 151-160.

Husebo, A. M. L., Karlsen, B., Allan, H., Soreide, J. A., & Bru, E. (2015). Factors perceived to influence exercise adherence in women with breast cancer participating in an exercise programme during adjuvant chemotherapy: a focus group study. Journal of clinical nursing, 24(3-4), 500-510.

Jerant, A. F., von Friederichs-Fitzwater, M. M., & Moore, M. (2005). Patients’ perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient education and counselling, 57(3), 300-307.

Kirkham, A. A., Bonsignore, A., Bland, K. A., McKenzie, D. C., Gelmon, K. A., Van Patten, C. L., & Campbell, K. L. (2018). Exercise prescription and adherence for breast cancer: one size does not FITT all. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 50(2), 177-186.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705.

Mackrill, T. (2011). Differentiating life goals and therapeutic goals: Expanding our understanding of the working alliance. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 39(1), 25-39.

Maddux, J. E. (2002). The power of believing you can. Handbook of positive psychology, 277-287.

Mantey, D. S., Omega-Njemnobi, O., Ruiz, F. A., Vaughn, T. L., Kelder, S. H., & Springer, A. E. (2021). Association between observing peers vaping on campus and E-cigarette use and susceptibility in middle and high school students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 219, 108476

Marien, H., Custers, R., Hassin, R. R., & Aarts, H. (2012). Unconscious goal activation and the hijacking of the executive function. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(3), 399.

Marshall, S. J., & Biddle, S. J. (2001). The transtheoretical model of behaviour change: a meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Annals of behavioural medicine, 23(4), 229-246.

Martin, R., & Murtagh, E. M. (2015). An intervention to improve the physical activity levels of children: design and rationale of the ‘Active Classrooms’ cluster randomised controlled trial. Contemporary clinical trials, 41, 180-191.

Martín-Borràs, C., Giné-Garriga, M., Puig-Ribera, A., Martín, C., Solà, M., & Cuesta-Vargas, A. I. (2018). A new model of exercise referral scheme in primary care: is the effect on adherence to physical activity sustainable in the long term? A 15-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ open, 8(3), e017211.

McAuley, E., Konopack, J. F., Morris, K. S., Motl, R. W., Hu, L., Doerksen, S. E., & Rosengren, K. (2006). Physical activity and functional limitations in older women: influence of self-efficacy. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), P270-P277.

McInnis, K. J., Franklin, B. A., & Rippe, J. M. (2003). Counselling for physical activity in overweight and obese patients. American family physician, 67(6), 1249-1256.

Merz, M., & Steinherr, V. M. 2021. Process-based Guidance for Designing behaviour Change Support Systems–Marrying the Persuasive Systems Design Model to the Transtheoretical Model of behaviour Change.

Mesters, I., Wahl, S., & Van Keulen, H. M. (2014). Socio-demographic, medical and social-cognitive correlates of physical activity behaviour among older adults (45–70 years): a cross-sectional study. BMC public health, 14(1), 1-12.

Michie, S. (2008). Designing and implementing behaviour change interventions to improve population health. Journal of health services research & policy, 13(3_suppl), 64-69.

Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., ... & Wood, C. E. (2013). The behaviour change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behaviour change interventions. Annals of behavioural medicine, 46(1), 81-95.

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation science, 6(1), 1-12.

Nikolajsen, H., Sandal, L. F., Juhl, C. B., Troelsen, J., & Juul-Kristensen, B. (2021). Barriers to, and facilitators of, exercising in fitness centres among adults with and without physical disabilities: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(14), 7341.

Ojo, S. O., Bailey, D. P., Brierley, M. L., Hewson, D. J., & Chater, A. M. (2019). Breaking barriers: using the behaviour change wheel to develop a tailored intervention to overcome workplace inhibitors to breaking up sitting time. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-17.

Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (2012). Strengths‐based cognitive–behavioural therapy: A four‐step model to build resilience. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 19(4), 283-290.

Padesky, C. A., & Mooney, K. A. (2012). Strengths‐based cognitive–behavioural therapy: A four‐step model to build resilience. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 19(4), 283-290.

Pappies, E. K. (2016). Health goal priming as a situated intervention tool: how to benefit from nonconscious motivational routes to health behaviour. Health psychology review, 10(4), 408-424.

Parks, M., Solmon, M., & Lee, A. (2007). Understanding classroom teachers' perceptions of integrating physical activity: A collective efficacy perspective. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 21(3), 316-328.

Pedersen, B. K., & Saltin, B. (2015). Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 25, 1-72.

Petrocelli, J. V. (2002). Processes and stages of change: Counselling with the transtheoretical model of change. Journal of Counselling & Development, 80(1), 22-30.

Pettit, J. A., & Karageorghis, C. I. (2020). Effects of video, priming, and music on motivation and self-efficacy in American football players. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 15(5-6), 685-695.

Plotnikoff, R. C., Costigan, S. A., Karunamuni, N., & Lubans, D. R. (2013). Social cognitive theories used to explain physical activity behaviour in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive medicine, 56(5), 245-253.

Resnick, B., Luisi, D., & Vogel, A. (2008). Testing the Senior Exercise Self‐efficacy Project (SESEP) for use with urban dwelling minority older adults. Public health nursing, 25(3), 221-234.

Resnick, B., Palmer, M. H., Jenkins, L. S., & Spell bring, A. M. (2000). Path analysis of efficacy expectations and exercise behaviour in older adults. Journal of advanced nursing, 31(6), 1309-1315.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68.

Ryan, R. M., & Patrick, H. (2009). Self-determination theory and physical. Hellenic journal of psychology, 6(2), 107-124.

Ryan, S., & Carr, A. (2010). Applying the biopsychosocial model to the management of rheumatic disease. In Rheumatology (pp. 63-75). Churchill Livingstone.

Schunk, D. H. (1989). Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning. In Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 83-110). Springer, New York, NY.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2009). Self-efficacy theory. Handbook of motivation at school, 35, 54.

Schwarzer, R. (2011). Health behaviour change.

Shaughnessy, M., Resnick, B. M., & Macko, R. F. (2006). Testing a model of post‐stroke exercise behaviour. Rehabilitation nursing, 31(1), 15-21.

Sheldon, K. M., & Houser-Marko, L. (2001). Self-concordance, goal attainment, and the pursuit of happiness: Can there be an upward spiral? Journal of personality and social psychology, 80(1), 152.

Slovinec D'Angelo, M. E., Pelletier, L. G., Reid, R. D., & Huta, V. (2014). The roles of self-efficacy and motivation in the prediction of short-and long-term adherence to exercise among patients with coronary heart disease. Health Psychology, 33(11), 1344.

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health psychology review, 8(1), 1-7.

Stadler, G., Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2009). Physical activity in women: Effects of a self-regulation intervention. American journal of preventive medicine, 36(1), 29-34.

Stone, G. A. (2018). The Neuroscience of Self-Efficacy: Vertically Integrated Leisure Theory and Its Implications for Theory-Based Programming. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 10(2).

Strecher, V. J., & Rosenstock, I. M. (1997). The health belief model. Cambridge handbook of psychology, health, and medicine, 113, 117.

Taylor, D., Bury, M., Campling, N., Carter, S., Garfied, S., Newbould, J., & Rennie, T. (2006). A Review of the use of the Health Belief Model (HBM), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and the Trans-Theoretical Model (TTM) to study and predict health related behaviour change. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 1-215.

Teixeira, P. J., Carraça, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. International journal of behavioural nutrition and physical activity, 9(1), 1-30.

Valente, T. W. (2015). Social networks and health behaviour. Health behaviour: Theory, research and practice, 5, 205-222.

Van Cauwenberg, J., Nathan, A., Barnett, A., Barnett, D. W., & Cerin, E. (2018). Relationships between neighbourhood physical environmental attributes and older adults’ leisure-time physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 48(7), 1635-1660.

Velicer, W. F., Norman, G. J., Fava, J. L., & Prochaska, J. O. (1999). Testing 40 predictions from the transtheoretical model. Addictive behaviours, 24(4), 455-469.

Velicer, W. F., Norman, G. J., Fava, J. L., & Prochaska, J. O. (1999). Testing 40 predictions from the transtheoretical model. Addictive behaviours, 24(4), 455-469.

Vinnikova, A., Lu, L., Wei, J., Fang, G., & Yan, J. (2020). The use of smartphone fitness applications: The role of self-efficacy and self-regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7639.

Volkmer, B., Sadler, E., Lambe, K., Martin, F. C., Ayis, S., Beaupre, L., ... & Sheehan, K. J. (2021). Orthopaedic physiotherapists’ perceptions of mechanisms for observed variation in the implementation of physiotherapy practices in the early postoperative phase after hip fracture: a UK qualitative study. Age and ageing, 50(6), 1961-1970.

Wagner, J., Burg, M., & Sirois, B. (2004). Social support and the transtheoretical model: Relationship of social support to smoking cessation stage, decisional balance, process use, and temptation. Addictive behaviours, 29(5), 1039-1043.

Webb, T. L., Schweiger Gallo, I., Miles, E., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2012). Effective regulation of affect: An action control perspective on emotion regulation. European review of social psychology, 23(1), 143-186.

Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation science, 4(1), 1-9.

Weinstein, N. D. (1993). Testing four competing theories of health-protective behaviour. Health psychology, 12(4), 324.

West, R. (2005). What does it take for a theory to be abandoned? The transtheoretical model of behaviour change as a test case. Addiction, 100(8), 1048-1050.

Westar, H. (2004). Managing resistance in cognitive behavioural therapy: The application of motivational interviewing in mixed anxiety and depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 33(4), 161-175.

Williams, D., & Rhodes, R. E. (2016). The Confounded Self-Efficacy Construct: Review, Conceptual Analysis, and Recommendations for Future Research. Health psychology review, 10(2), 113.

Wilson, K., & Brookfield, D. (2009). Effect of goal setting on motivation and adherence in a six‐week exercise program. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 89-100.

Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E., & Grattan, K. P. (2008). Understanding Motivation for Exercise: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 250-256.

Zimmerman, G. L., Olsen, C. G., & Bosworth, M. F. (2000). A 'stages of change' approach to helping patients change behaviour. American family physician, 61(5), 1409-1416