A passion for client centeredness

My dissertation:

What are the experiences of person-centred support for people living with long-term health conditions including those who are underrepresented in society?

To protect client confidentiality I cannot post much of my dissertation as it was interview based, so I have cherry picked the highlights and uploaded my literature review. I originally intended to to do my dissertation on “How could adherence to exercise and lifestyle reprogramming be improved for all breast cancer survivors including women from disadvantaged backgrounds?” building on my time spent in prehab and rehab for Cancer recovery alongside previous literature reviews and my cancer research proposal, but I struggled to find my way, and after some mentoring with my incredible tutor -John Downey, he worked with me to find my core beliefs, values and where I usually gravitate in all my research projects and we found that person centeredness was at the heart of all of my beliefs, values and the foundation of my work.

Abstract

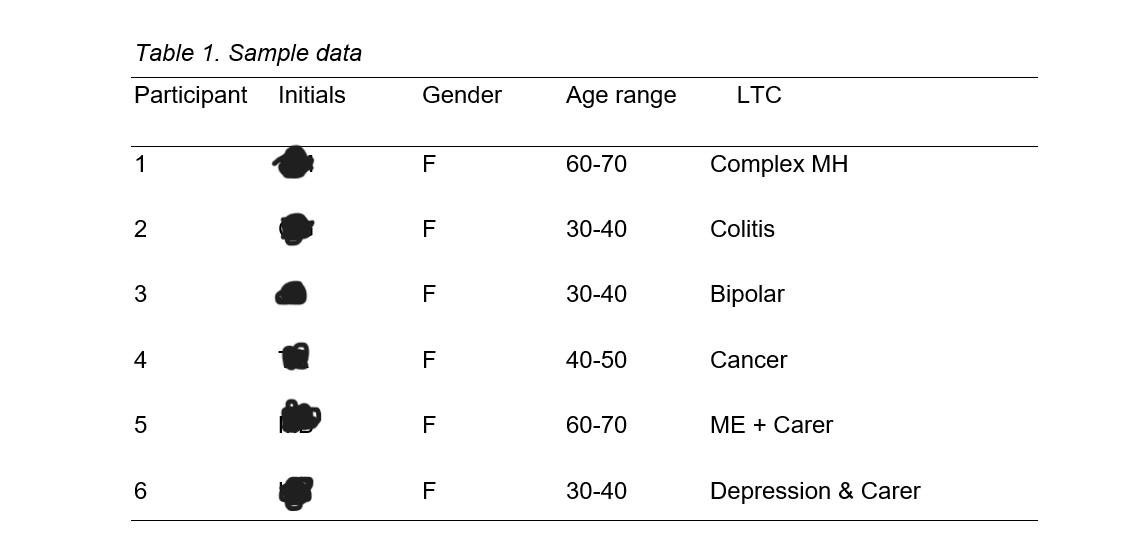

Person centred support is an approach used in healthcare, support services and more recently gained awareness within communities which places the individual at the forefront or decision making, recognising the unique needs and preferences of the individual. The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of person-centredness for people living with long-term conditions in healthcare, the community and within family settings, including people from disadvantaged backgrounds. The six interviewees, selected through purposive / judgmental sampling, aged between 30-70 completed a m= 64.6m (SD 8.668), semi structured interviews, to collect qualitative data of first-hand experiences of individuals stories and encounters from diagnosis to the present day. The researcher used, The Braun and Clarke (2006) model of thematic analysis to analyse the data until saturation, forming three overarching themes: Experiences of the person-centred system, Community person centred experiences, and barriers to positive self-management and wellbeing.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1 Long-term Health Conditions

LTC’s are chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hormone driven Cancers and other inflammatory diseases which develop over the course of many years; often due to multiple lifestyle factors (Sørensen et al.,2020) including diet, exercise, stress, health factors such as side effects of other medications, disabilities, MH issues and social factors including poor housing and a lack of green space. Poor air quality from traffic and industrial emissions, have been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, heavy metals and polluted drinking water, pesticides and hazardous materials increase neurological disorders and cancer, and hazardous waste and substance exposure from occupations such as building and mining contribute to respiratory and cancer conditions. (Kampa & Castanas, 2008: Cockerham et al., 2017). LTC’s do not have a cure but can be managed and put into remission with lifestyle intervention, medications, and support (Taheri et al., 2020). However long-term adherence is a significant problem (Sjöström, 2013).

According to the NHS, around 70% of the healthcare budget is spent on managing and treating chronic conditions. In 2019, the UK spent £50.5billion (McPhail, 2016: Smith et al., 2012).

2.2 Underrepresented in society

Research has highlighted that individuals who are underrepresented in society are more likely to have co-morbidities, and less likely to receive PCS (Williams & Mohammed,2013). Today, the most SES deprived adults under 65 have significantly greater multimorbidity’s than adults with high SES and the statistics are increasing exponentially, forecasted to increase to 68% by 2035 (Soley-Bori et al.,2021: Barnett et al., 2012). Furthermore, at least one of those conditions is most likely a MH issue, which has been shown to worsen in correlation with the number of physical conditions diagnosed. (Gunn, 2012).

PCC is essential for individuals from DAB with LTC’s (Fors et al., 2016). According to research, they do not respond well to 15-minute time slots, health literacy, letter comprehension, portraying mistrust of systems, and difficulties finding a voice with authoritative people in clinical settings. (Hibbard & Greene, 2013: Chen & Yang, 2014: Williams et al., 2019). Individuals living in temporary accommodation with social deprivation are known to experience difficulties to engage, remember appointments and process information (Williams & Mohammed, 2013) Poor Living conditions are expected to deteriorate this winter for people in those circumstances, with further stark forecasts of additional individuals losing their homes in a problematic housing system, will likely increase the number of people falling into poverty and exacerbate difficulties with PA and the SE of conditions for more people. (Grover et al., 2021: Clark et al., 2018).

As the government pushes for a preventive care model, people with LTCs who need the intervention the most are at risk of further health discrimination, marginalisation, and likely receiving less PCC than their affluent peers. (Clark et al., 1999: Krieger, 2000: Fiscella & Epstein, 2008). GP’s have no control over the model in which they are required to operate and need support in the form agencies to refer too, who do have the time and training to work with the holistic needs of patients, leaving them to assess and treat physical health presentations (May et al., 2004).

2.3 Primary and Secondary Care Settings

The definition and terms used for person-centered care amongst scholars and health professionals lacks consensus (Kitson et al., 2013). There are on-going debates regarding the appropriate terms which are interchangeable depending on the setting and professional experience of the health care professionals (Mead & Bower, 2000). According to Beresford (2011). PCC operates within primary care; PCS is a term used widely in secondary and voluntary services, such as physiotherapy, Social Prescribing, Pharmacies and community interest projects or charities. They both focus on the individual and their SM of health conditions and wellbeing (Ilardo & Speciale, 2020: Pulvirenti et al., 2014). A patient is described as someone who suffers and requires a health specialist to treat the disease. The relationship of power between the specialist and patient is unequal: the patient sits in dependency and vulnerability (Eklund et al., 2019). The PPC model’s aim is to incorporate the desires, values, and beliefs of the person into care decision-making. Individuals are encouraged to play an active role in designing a treatment plan congruous to them. It must promote individual autonomy and empowered choice, as well as incorporate a holistic care approach that addresses all aspects of a person's multidimensional well-being (Rogers, 1995: Taylor et al., 2018).

Historically, the NHS used the biological model and adopted a paternalist approach to care, whereby, knowledge, jargon health language and power sat with the professional who had a role to apply health interventions and education to the individual, designing care packages with no involvement of the patient (Kogan et al., 2016). However, since the late 1960s, the doctor-centred model has come up against much criticism and PCC language and implementation has been on the increase since the twentieth century (Taylor et al., 2018). Although observations have highlighted a lack of understanding of the core values, given rise to meaningless slogans and superficial implementation much like front of house roles in expensive hotels (Epstein & Street, 2011). The dissatisfaction of patients has grown since the 1970’s. Patient complaints regarding the power held by doctors have mounted over the years (Stewart, 1995), highlighting disregard for patients innate wisdom of their own bodies and preferred SM, showing a lack of humanistic interactions (Chen et al., 2021). Criticism of health language / jargon used and a lack of willing negotiation of the treatment pathway options have been highlighted (Levinson et al., 2010: Ferguson & Candib, 2002: Lee et al., 2002) and more recently the age of technology has given every individual the opportunity to research and learn about health conditions and SM (Tu et al., 2019).

This has led to a widening inequality gap whereby those who have disposable time, finances and cognitive bandwidth, can afford preventative care, access healthy food choices, enjoy activities which reduce stress and access support networks, are also more likely to feel empowered to ask for the treatment pathway they desire, ask questions and converse in health language to ensure the best health outcomes within primary Care (Cooper et al., 2011: Pollak et al., 2010: Buyens et al., 2022). The biopsychosocial perspective allows the health professional to view the condition and how the patient experiences the illness (Bouchareb et al.,2022). The willingness of the care professionals to consider individual’s varying perceptions of pain, their identity, attachment, and perceived life changes due to illness and many social factors known to impact SM and patient engagement (Hadi et al., 2017) has shown to increase patient satisfaction, the ability and motivation to self-manage their condition (Oftedal et al., 2010: McCarley, 2009).

In a study assessing the value of supporting patients living with Type 2 diabetes and multimorbidities for at least two years active SM through the constructs of the self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012), noting the three main constructs needed for SM and motivation are feeling competent to achieve the goal, self-autonomy, and relatedness (Powers et al., 2015). Previous studies highlighted the need for emotional support for the 50% who reported SM difficulties due to increased stress experienced as part of living with long-term diabetes (Sorenson et al., 2020). The three main themes from the 11 individuals were being listened to by a health care provider that they had built rapport with, using a two-way dialogue including time to talk about their experiences and lived impact of the condition with compassion, as opposed to reported primary care giver’s closed questions and domination of knowledge from specialists predominately doing the talking: as shown in other studies (Kwame & Petrucka, 2020). One patient said they found the holistic intervention so effective that they no longer needed counselling for their depression (Moudatsou et al., 2020). Another study found connectedness, involvement and attentiveness as the top themes wanted from patients (Marshall et al., 2012). The study did however highlight resistance to autonomy and felt the primary care were responsible for educating them about SM and many were resistant to lifestyle changes also found in other studies (Shi et al., 2020: Portz et al., 2019) but did appreciate self-monitoring glucose devices useful (Sorenson et al., 2020). Overall, the study concluded that patients wanted to talk about themselves holistically and responded to 40-60min appointment times to discuss coping strategies and receive positive empowering health promotion (Sørensen et al., 2020). Other studies have highlighted that focusing on patients’ qualities and attributes would yield further SM success (DuBois et al., 2012).

2.4 Person-centred support - bridging the gap.

Secondary care and third sector agencies may have more time to work with the persons values and desires viewing their psychology, narrative, emotional needs and fears, their behaviour history, positive and negative pain management strategies, and their psychosocial experiences (Coventry et al., 2014: Miles & Asbridge, 2016). Recently the NHS’s investment into Social Prescribing (SP) as one of the six pillars has further increased behaviour change support for patients living with LTC and GP’s have the option to assist with the clinical needs of the patient and refer to the social prescriber to support patient’s SM with behaviour change counselling, goal identification and connection to third sector agencies for lifestyle change support (Baska et al., 2021). Although the evidence for cost effectiveness is mixed. There are criticisms of the ambiguousness and lack of guidance for interventions and follow ups as well as a research gap pinpointing the effective active ingredients of Social Prescribing (Cooper et al., (2022).

Barriers to delivering PCC have been reported in many studies such as burnout, job dissatisfaction, low staff morale and many staff reported a lack of training and sense that counselling is not part of their role (Willard-Grace et al., 2014: Esmaeili et al., 2014). However, studies have evidenced increased job satisfaction, patient outcomes / relationships, and increased longevity within the role when staff were able to practice PCC (Edvardsson et al., 2011: Lewis et al., 2012).

2.5 Person-Centered Approach (PSA) in the Community

The Person-Centered Approach (PSA) best describes interactions within the community, within families, friendship groups, churches, and paid services. Community engagement projects / psychologist’s emphasis shifts from the individual person and disease to supporting families and wider communities to operate from an equal, respectful place (Beadle‐Brown et al., 2012). The community may be educated on the awareness of self-management of conditions, awareness of the needs of people living with LTC’s, moving away from labels and stigma and guiding communities to find innovative ways to support those with health needs in a way which is autonomous to them, giving all an equal voice (Kato et al., 2016).

2.6 Person Centeredness

PC has also been identified as an important concept in the context of care provided by family and friends to people living with long-term conditions (Zimmerman et al., 2014). Family and friends' involvement in the care of people with LTCs can have a significant impact on the individual's QoL and overall health outcomes (Vassilev et al., 2014). PC in care provided by family and friends can improve a person's QoL overall health outcomes (Kokanovic, & Manderson, 2006). A study found that involving family and friends in the care of people with LTCs can lead to improved medication adherence and better symptom management (Eaton et al., 2015). Furthermore, PC in care provided by family and friends can foster a more collaborative relationship between the person with LTCs and their carers, resulting in improved communication and shared decision-making (Kristianingrum et al., 2018: Jovanovic et al., 2022). It is worth noting that families can also hinder SM and some relationships may be detrimental (Trivedi, & Asch, 2019). PC may increase a person's sense of autonomy, which is especially important in the context of LTCs, where people may feel a loss of autonomy of health (Bao et al., 2022). However, there are challenges to implementation of PC which include a lack of training and support given to carers, who are often overburdened and at risk of developing ill health and reduced mortality overtime (Nascimento et al., 2022). Individuals living with LTC’s have reported experiencing stigma, discrimination, a lack of understanding about their condition, as well as Isolation and inequalities within the community (Chlebowy et al., 2010). A study found a gentleman with Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease reported they felt unable to be part of community activities due to stigma and a lack of social support (Johnson et al., 2007). Difficulties accessing health and social care due to stigma further impact health conditions in individuals with LTC’s which was also highlighted in a study by a group living with MH conditions (Ali et al., 2013), although there are many cases where people with LTC’s have expressed a sense of belonging and receive social support from peer-led groups making their communities a positive experience (Missel et al., 2019). Community experiences are affected by many factors, studies have highlighted a lack of choice as a significant factor (Ogunbayo, et al., 2017). A study found that individuals living with diabetes experienced a lack of food choice when meeting social groups, leading to difficulties managing blood sugars and limiting their choice for social interactions (Mathew et al., 2012). Furthermore, choice to access pain management clinics is low, leading to isolation and increased poor MH and reduced QOL (Deslauriers et al., 2021). However, there are studies reporting positive experiences of social inclusion and choice, when the right support, education and resources are accessed (Pinkert et al., 2021). Another study found that by taking the individual’s preferences into account, it improved the persons QoL, improved health outcomes and reduced hospital admissions, although this is not found in all studies, emphasis on adapting communication styles to the preferences of the individual would be beneficial (Rodin et al., 2009). Furthermore, SM programmes within the community, education for community staff on the development of community programmes may be beneficial (March et al., 2015). Moreover, PC approaches which empower people to take an active role in the management of health conditions lead to improved self-efficacy and health management skills. Studies have shown that programmes developed in partnership with individuals to support SM skills according to their individual needs are more effective (Shaw et al., 2013: Hibbard & Greene, 2013). Recognising how challenging it can be living with LTCs and understanding the significance, empathy and compassion has on individual’s well-being. It is often highlighted that support is required to integrate individuals into appropriate groups to overcome barriers, promote self-confidence and help settle individuals before withdrawing support (Moffatt et al., 2017), an element which is missing in social prescribing support based in clinics, rather than the community (Husk et al., 2020). However, there are barriers to implementing community programs such as funding shortages, skilled staff, and resources (Greenhalgh & Montgomery,2020)

There is a need to increase awareness of what person centeredness means as a concept as well as how beneficial it is to the person receiving it within communities (Wilkinson et al., 2019). The day to day living experiences within community activities, church groups and services significantly impact on QoL and self-management, as this is where people spend most of their lives (Ruggiano & Edvardsson, 2013). Building awareness of PC into mainstream activities and communities would enhance and strengthen communities (Waters & Buchanan, 2017). Intermate services such as hairdressers, coffeeshop / supermarket staff, and beauty therapists build relationships over-time and are in an advantageous position for being an invaluable source of support and peer learning (Page et al., 2022). They can provide social PCS and health promotion according to their individual needs (McCormack et al., 2010). The church community have provided community support and cohesion throughout history, although significantly less over the years, they do play an integral supportive role in small communities for the aging populations, often involved in foodbanks, soup kitchens and rough sleeping support, their salutogenic approach is concerned with health and well-being in the community (Kennedy & Stirling, 2019).

2.7 Conclusion

PCS delivery is often unequal in Primary care (World Health Organization, 2015). Factors that affect PCS are the type of condition the individual is living with (Schabert et al., 2013: Crompvoets et al., 2022). the hospital department, funding, staffing levels and morale (Scerri et al., 2020), the SES of the patient, health literacy and personality traits of the patient (Schmidt et al., 2002: Epstein et al., 2005). Studies have shown that PCS improves quality of life, well-being and supports self-management of conditions and goal setting (Russell et al., 2018). staff who show genuine empathy and compassion have been highlighted in many qualitative studies to positively impact the health and well-being of patients, especially those who have multi-morbidities with one being a MH problem (Malenfant et al., 2022). Social prescribers could play a vital role as an advocate and mediator for individuals who do not have health literacy, giving them equal opportunities within primary care, linking to community health and wellbeing activities within the communities and supporting the removal of social, physical, and practical skill barriers to participation (Smith et al., 2009: Samerski, 2019).

Person centeredness is an approach which respects, values, individual choice, and see’s the person holistically, not just the condition, and works in partnership with the individual, to discover their motivations for change and adherence to healthy lifestyle practices to improve their QoL (Gagliardi et al.,2021). Research has shown that by mobilising person-centred social support, individuals could access community interventions to overcome physical, psychological barriers and enhance SM skills which may reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness (Russell et al., 2018: El-Etreby et al., 2019). Community centred interventions which take the lead from the patients, asking both what they need and their desired outcomes for the interventions; are shown to be more successful to support QoL than educational programs set by professionals which are evidenced to have poor outcomes due to the tone of delivery and the research highlights that people often know what behaviours are healthy, and often need support to work through inner conflicts, find their intrinsic motivations and access peer support and comradery (Stansfield et al., 2020: Van de Velde et al., 2019: Angwenyi et al., 2018: Markland et al., 2005: Wildman et al., 2019).

This review highlights that the individuals who need PCS the most are the least likely to receive it in many cases, however many studies have highlighted the recent positive changes with the investment of Social prescribing, health coaches and a variety of community interventions from councils, charities and community interest projects all contributing to raising awareness of challenges and barriers individual’s with LTC’s live with and how person-centred delivery of community interventions increases well-being (Holding et al., 2020). Schmidt et al., 2002: Epstein et al., 2005).

Chapter 3 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

The researcher chose six people to interview for qualitative analysis, to hear about their perceptions of living with lTC’s and their experiences of interactions within healthcare and the community. The researcher chose qualitative data, semi-structured interviews to extract detailed, nuanced data from six participants, attending m= 64.6m (SD 8.668) interviews, to be analysed thematically.

The methodology was grounded in constructivism theory, with the aim to understand and explore the participants’ realities; it allows a depth and richness of the participant living with lTC’s (Mills et al., 2006). The researcher gained insights into the journey participants experienced living with LTC’s and the impact of experiencing person-centredness on self-management and QoL. The methods are a qualitative design, with a very small amount of quantitative data used to support a theme when required. However, it is merely to suggest the strength of a theme, not to distract from the qualitative design (Walliman, 2014: Wiltshire & Ronkainen, 2021).

3.2 Sample

The researcher recruited six participants using purposive / judgemental sampling, selecting participants based on their lived experiences of LTC’s. This approach is commonly used in qualitative studies (Campbell et al., 2020). A 5-20 sample can provide enough quality data for analysis however, this is not always true (Marshall et al.,2013), Smaller studies can provide understanding of human complex perceptions and experiences, therefore, 5-20 participants can achieve data saturation (Charmaz, 2006)

The project provides 6 female adults, aged 30-70, living with LTC’s, who were recruited through social media and word of mouth. The researcher’s desire to interview participants from disadvantaged backgrounds were limited due to practicality and the potential to cause distress. Each participant was provided with written details of the study’s aims and procedures, and a consent and consultation form (Appendix B&C).

3.3 Protocol for Data Collection

The interview dates and times were arranged with the participants and care was taken to provide a confidential meeting point which was conducive to feeling relaxed and comfortable to talk freely. The interviewer went to the arranged location and conducted the interviews which came to a natural end, the mean time was 64.6m. The interviews were recorded using a EVISTR voice recorder. The semi structured narrative interviews were conducted. The researcher used an interview guide and actively listened, validated, and prompted, guiding with open ended questions (Staller, 2022). The researcher then transcribed the interviews 1-6, each interview was 50% transcribed and edited using Otter AI and 50% hand transcribed into word. The semi structured questions were prepared ahead of time, and questions rarely used so that the client could chronologically describe their experiences (Adams, 2015). Semi structured interviews provide the opportunity to dive deep into a participant’s experiences. It offers flexibility and opportunity to discover unexpected themes and allows the researcher to probe into meaningful narratives. It prioritises the participant’s voice, allowing the researcher to follow and acknowledge a unique account of the participant’s lived experiences and goes beyond superficial responses, providing social, cultural, and personal contexts which shape the participant’s perspectives and experiences (Dearnley, 2005). The researcher interacted in a person-centred manner, supporting the participant to feel safe to tell their story without fear of judgement (Sandvik & McCormack, 2018). Semi- structured interviews were helpful to gently guide the participant back to topic when required (Whiting, 2008).

3.4 Data Analysis

The study used a qualitative approach in the form of semi structured interviews, using prompts and open-ended questions (Appendix E). Once the data had been transcribed to a word document the researcher used Thematic Analysis to code the raw data. The researcher familiarised themselves with the data, adding line by line coding initially (Appendix E). The researcher was careful not to use a reductive method to ensure nuance was maintained (Guest et al.,2011). This process was repeated until saturation (Lowe et al., 2018). The researcher then created themes and sub themes to systematically organise the data, highlighting patterns and evaluating throughout the process (Maguire & Delahunt, 2017). Using MS Word’s comment feature the researcher organised a themes table (Appendix E2), organising, reviewing and deleting the line-by-line coding and applying extracts to codes as the final version of data in line with the research aims (Marshall, 2019).

3.5 Ethical Considerations

Each participant received a casual verbal discussion regarding the project aims and a detailed written explanation of the projects aims, how the data will be used, personal anonymity protection, and safety information if a participant is emotionally triggered. The form explains that participants can stop at any time for a break or to opt out completely at any time (Arifin, 2018). each participant signed for consent (Appendix C). The consultation form (Appendix C.1) asked for details of any acute health issues which may impact the interviewees and to sign a deceleration of good health. Care was taken to build rapport and trust prior to the interviews, to ensure participants felt safe to tell their stories (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Ethical guidelines were followed by the researcher throughout the study. An ethical approval from Marjon was obtained before starting the research project (Appendix A). All participants were adults. Confidentiality has been maintained by removing the clients’ names, leaving an initial (Kaiser, 2012). The recoded data was used on a password protect PC, and destroyed once transcribed (Iversen et al.,2006). The researcher made the decision not to interview three people who they felt were too vulnerable and may be at risk of further distress, in line with the code of ethics (Smith, 2003). Furthermore, the decision to not wholly target people from disadvantaged backgrounds was made for ethical reasons (Allmark et al.,2009). There were no invasive physical interventions and care was ensured to explain the emotional process the participants would go through before interviewing and supported the interviewees throughout the process.

3.6 Reliability and Validity

Absolute reliability and validity are fundamental considerations in research methodology. They help ensure that the results and conclusions of a study are accurate, consistent, and trustworthy (Rose & Johnson, 2020). There are a number of ways to ensure validity of qualitative research, ensuring credibility and trustworthiness of interpretation (Golafshani, 2003). The researcher ensured to use various strategies to enhance the validity. Reflexivity was used to work through the researcher’s own biases by ensuring the participants knew they weren’t looking for an answered question, merely a story of their experiences from the beginning (Jamieson et al.,2022). Saturations was achieved by analysing the data until no new information emerged, capturing the complexity and depth of the investigation (Saunders et al., 2018). Detailing the process of analysis for evidence for transparency and scrutiny (Shufutinsky, 2020). Seeking peer debriefing and review from people familiar with qualitative research supports critical analysis from several viewpoints and enhances the validity of findings (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

3.7 Limitations

Qualitative data analysis done by hand is a considerably long process, leaving the results open to human error and emotional interpretations. There are known potential biases and considerations which affect the integrity of the study, such as critical self-reflection and evaluation, the ability to conduct a person-centred interview with minimal influence on the participant’s narrative, positionality explained to the participants to encourage open dialogue, ability to build rapport and interviewer neutrality, avoiding leading and suggesting questions which may influence participants’ answers.

The study did not involve triangulation which may have enhanced its rigour and mitigated biases further. Peer debriefing to review data, reduce bias (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Furthermore, the researcher was unable to interview the hard to reach in society due to ethical considerations. The final sample was six interviews; more interviews may have provided further patterns and themes to support the findings (Marshall et al., 2013).

3.8 Delimitations

The semi structured interview questions are within the focus and scope of the study’s aims and literature review, including a scoping review of papers from the last 10 years. Sample delimitation supported the purposive / judgemental sampling technique due to the perspectives of people living with LTC’s being crucial to the study. Semi structure interviews were conducted to hear rich, complexed narratives around LTC management. The researcher experienced hard to reach data as a constraint.

Chapter 4 Results and Findings

4.1 Introduction

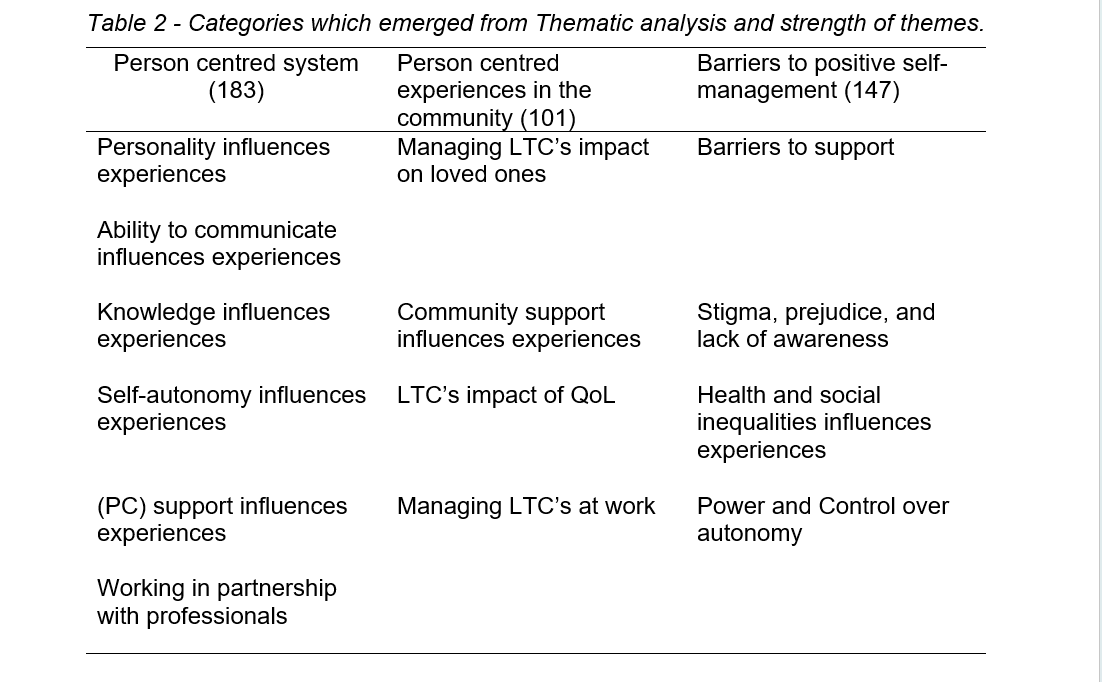

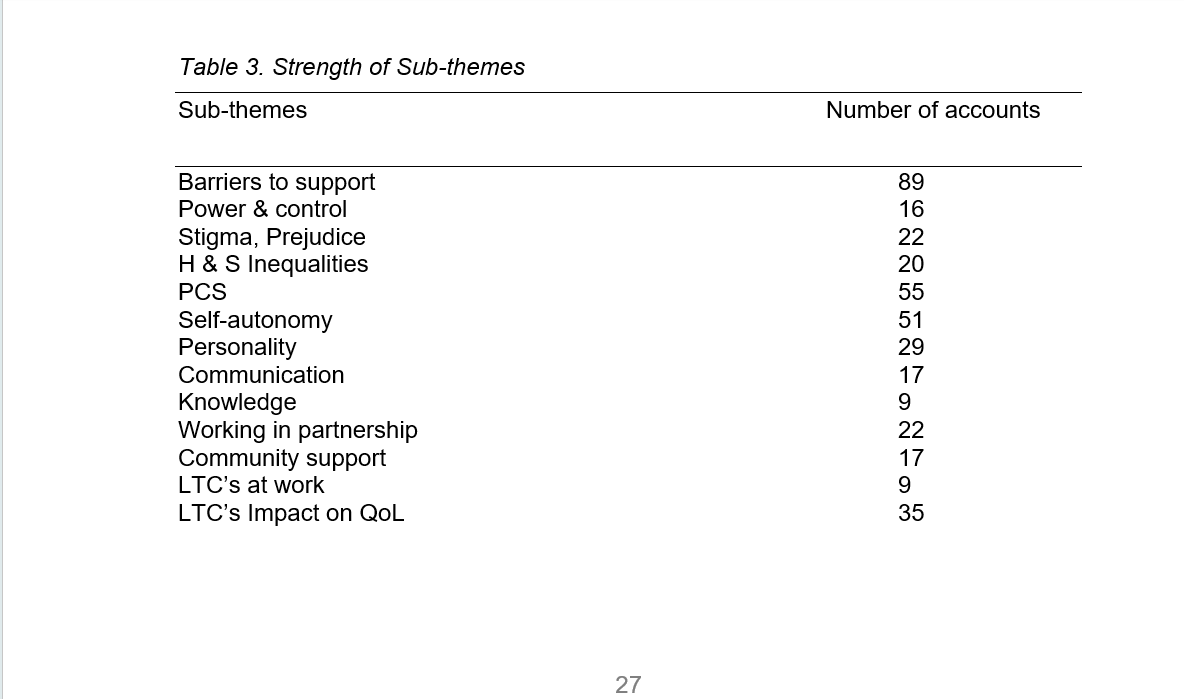

The chapter will display the main findings of three main themes and 12 sub themes (shown in Table 2) which emerged from thematic analysis. These themes were the lived experiences of six individuals.

The three themes which emerged from the data analysis illustrated the Barriers to positive self-management, which centered largely around barriers / lack of support, which was the largest mentioned sub-theme. Further barriers were separated into stigma and inequalities see Table 2. Person-centred experiences in the community contained insights into experiences of managing relationships, community groups and the impact on QoL see table 2. The third theme captured the stories of received PCS, the narratives highlighted the sub-themes of personality, communication, knowledge, self-autonomy and working in partnership as significant factors of person-centred interactions. See table 2.

4.2a. Barriers to positive self-management

The individual perceptions of the barriers to support, highlighted interactions in schools, friendships, community activities, and healthcare. Barriers to support centered around a lack of support, voiced through statements such as “They didn’t listen to me”, “the advice wasn’t practical for my lifestyle demands”, “I wasn’t believed” (Appendix E.2). One participant told a story of her 15-year battle getting adequate support for her daughter, who has a serious heart condition and processing difficulties due to oxygen starvation at birth. They endured a 7-year delay on an education-psychology assessment, the recommendations made were ignored by the school, affecting their MH.

The following quote illustrates the frustration and desperation the lack of support has caused.

“……the only thing I am aware of ATM is she may get extra time in exams. And that’s it. But it’s just a constant fight all the time, all the time and its exhausting, I shouldn’t have to fight all the time, but if I don’t fight for her who will………

(Appendix D.6)

4.2b Power and control over autonomy

Barriers to SM include power and control over autonomy, this subtheme described many historical power issues within mental health, which has improved. The participant tells a distressing story of power abuse within mental health institutions, which evidently left no will or confidence to self-manage her condition. It is important to note that she now has many accounts of person-centred improvements within the system and actively sits on panels to further improve PCS.

4.2c. Stigma, prejudice, and lack of awareness

Most accounts were historical within healthcare, however there were patterns around a lack of awareness prevalent today in the community, which were none the less distressing. These accounts involved MH and Colitis. One participant was told by a family member that she should stop drinking coke and that would solve the Colitis, another family member told the entire table whilst out for a meal that she was hiding food in her bag (the meal was too large for her to eat without distressing symptoms), these experiences impact future decisions to interact with the community. Poor experiences lead to isolation, detrimental to successful SM.

4.3. person-centred system

4.3a Self-autonomy

The person-centred theme predominantly talks about the many positive accounts which have improved their self-confidence and encompasses sub-themes separating characteristics of the theme. Self-autonomy highlighted many accounts of how choice was imperative to be able to SM their conditions. Participants described varying positive accounts, the standout story was the change in MH to incorporate family and friends into care plans and multi-agency meetings, where the patient is at the apex and gets to choose who they want to involve and remains at the forefront of the Future-plan.

4.3b. Personality traits, Ability to communicate and Knowledge

According to research personality factors influence the likelihood of receiving PCS. The results illustrated the need to have strong and assertive personalities to get their needs met and those who couldn’t speak up for themselves did not.

The following quote describes the need to be assertive at work to get mental health support.

“I’ve certainly seen a lot more support from my line manager, but I have seen some of the other girls from the other department have not has such good support, so I think my assertiveness and knowledge has helped”.

4.4. Person-centred experiences in the community

4.4a. Community support and managing LTC’s at work

It was evident as the patterns emerged that community support varies depending on the condition of the individual, for example the participant with a diagnosis of cancer experienced a wealth of support both emotionally and practically, she was also offered a variety of community groups and felt incredibly cared for throughout, in the community and at work. The experiences for people living with MH found difficulties accessing mainstream activities, describing barriers of self-consciousness and fear of stigma as well as unwilling to financially commit to the trend of upfront termly fees for activities, due to the likelihood it may not be suitable or that they have an acute episode and lose their money (appendix D3).

The stories told in this section highlights the strength and resilience of the individuals. LTC’s requires emotional and mental endurance, shaping personalities through adversity, often feeling alone and unsupported. The impact spans across relationships, community, work, and SM, requiring increased mental energy to creatively overcome obstacles daily, the stories paint a picture of exhaustion and dark periods of loneliness. The stories also indicate that overcoming self-rejection is part of the journey, loving oneself is difficult for many, but particularly for individuals with LTC’s who experience complex and trying symptoms. Demonstrated by one participant who describes being rejected by her family when her parents passed away at a young age, she was diagnosed with bipolar many years later, but did not receive the support needed, she describes her relationships as difficult and often confrontational, leading to self-isolation from the community due to a lack of trust and trauma.

The following quote describes the difficulties experienced, which impact QoL

“……… I find that people can cope with you being a certain way, for a certain amount of time. But I've had a lot of friends that have sort of fallen to the wayside because, and I've had it fed back to me before that I'm high maintenance or whatever. And I've always kind of wondered how that is because actually, when I’m unwell, I become quite introverted. I stopped talking to people and I shut myself down………. (Appendix D3).

Chapter 5 Discussion

5.0. Introduction

The literature review found an extensive body of supporting evidence of positive outcomes when PCS is practiced. My project synthesized the key elements of the experiences of person-centredness and living with LTC’s, both positive and negative. Despite the participants living with different health conditions, they all shared commonalities in their desire to receive self-humanistic qualities of person-centredness in their daily experiences. There were differences in the impact on daily living, attitudes towards their experiences and treatment received. The participants chosen, varied in SES, demographics and ranged between 30-70 years of age, which enabled rich life stories to unfold.

5.1 Barriers to positive self-management

1a Barriers to support

This subcategory has the largest body of data, as the stories unfolded it became evident that the participants had many accounts of being ignored and were given standard advice which did not suit the demand and responsibilities placed on them. The participants felt discounted and un-cared for, the chronic lack of support spans across health and social care, school, friends, and church communities. Social cognitive theory suggests that individual behaviour is influenced by personal factors, environmental factors, and interactions with others (Zare et al., 2020). One participant was ignored and sent to various professionals, being made to wait six weeks, whilst suicidal. She was forced to go private to ensure she doesn’t experience that level of deterioration again, despite the cost. This is an unlikely option for low SES groups, suggesting they experience a higher number of inequalities (Blundell et al., 2020).

Several accounts were regarding the barriers to the personal independent payment (PIP). The narrative described the powerful assessor lacking in compassion or unwillingness to display any person-centred qualities, evidenced in many studies to be detrimental to wellbeing (Webb & Albert, 2022: Clark et al., 1999: Krieger, 2000: Fiscella & Epstein, 2008). One individual described her experience involving her local church community. She was shocked and hurt that no one made any contact during COVID lockdown, leaving her feeling alone and experiencing an identity crisis. The biopsychosocial model acknowledges the complex interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors of well-being. Isolation and lack of support are considered psychosocial factors that can impact an individual's ability to manage their condition effectively (Shantz & Elliott, 2021). Previous literature highlights how community PCS including family support can help individuals with LTC’s improve SM. This is also supported by the Social Support Theory, especially in those from DAB (Lakey & Cohen, 2000: Kokanovic, & Manderson, 2006: Eaton et al., 2015: Eaton et al., 2015: Kristianingrum et al., 2018: Jovanovic et al., 2022).

The quote describes the lack of support and awareness from the church groups, during and post COVID.

“Yes, I feel quite hurt by it. I used to go every week, ………………. they said Well you took yourself away, you isolated yourself. I had no choice though, why didn’t they reach out to be? ……….

(Appendix CG)

5.1b. Power and control over autonomy

Power imbalance theory highlights that unequal power in a relationship undermines patient autonomy and impacts the ability to SM furthermore, the experiences are more likely to be experienced by those from DAB (Drury et al., 2020). Many accounts of power and control were historical MH systems, who in her words yielded power over where they lived, the relationships they had and they were not interested in her views, wishes, or needs. Control theory suggests that when an individual’s autonomy is compromised during treatment plans or forced to do things they do not wish to, it undermines motivation and ability to effectively SM (Buchmann et al., 2021).

The following quote describes the power of past MH services, which has changed significantly.

It’s like being a five-year-old again, and it compels you to want to rebel, you want to speak out and tell them about how much control they have over you (angry), sometimes when you're depressed, and your mood is so low it makes you give up because you can feel like you're just being totally suffocated……………. (Appendix D1)

Other stories speak of accounts where the professional holds the power and will not listen or engage in reasonable action, regardless of the suffering. One participant is a carer who also experienced an acute bout of ME after a relationship breakdown, where the GP treated it like a MH problem, disregarding her symptoms (Appendix D.5). As a carer she and her current husband applied for PIP, the assessor said as her husband who had COPD wasn’t out of breath (because he arrived in a wheelchair with oxygen) he was not entitled. Power and control creates feelings of frustration, defeat and impacts self-worth, The self-determination theory emphasises the need for intrinsic motivation for SM, as demonstrated in many studies (Stenberg et al., 2022: Ntoumanis et al., 2021).

5.1c. Stigma, prejudice, and lack of awareness

Interviewing individuals with a variety of LTC’s demonstrated that stigma and prejudice is directed at MH conditions and lesser understood conditions such as ME and Colitis. Invisible diseases attract much criticism and mis-placed opinions in the community but also from trained health professionals (Taft & Keefer, 2016). Stigma destabilises social identity; it undermines and devalues individuals. Internalisation of stigma creates further despair and poor mental well-being which impacts QoL (Setchell et al., 2023). Positive PC interactions are validating, often people with conditions such as MH, find it difficult to understand and accept their condition, but when professionals interact in a humanistic manner they validate the individual’s symptoms, thus motivating them to SM. This is supported by the humanistic theory and shown in other clinical studies (Dineen-Griffin et al., 2019: Arboleda-Flórez & Stuart, 2012: Dineen-Griffin et al., 2019).

5.1d. Health and social inequalities

Participants described perceived inequalities in school, disparities between excellent cancer care and the dissatisfaction of MH services also mentioned by another participant with a MH condition, who feels the inequalities affects her (appendix D3 pg28). Health and social inequalities affect people from DAB disproportionally. They require targeted health promotion and support to overcome barriers such as geographical and health literacy to access services and community. The staff’s attitude can create inequalities and should become aware of unconscious biases, have a good awareness of diverse cultures, beliefs, and practices. The social determinants of health theory says that health outcomes are influenced by socioeconomic factors, which leave individuals vulnerable to further inequalities.

The following quote spoke about how support depends on the worker’s attitude. The full story is (appendix D.1)

“…… there is an issue where it depends how stressed out the worker is, and how much caseload they've got. I can give you a good example, a friend that we used to have years ago, and he was admitted on a section and his disability living allowance came up and because he was so poorly, he decided there was nothing wrong with him. So, he filled in the Disability Living Allowance saying I'm fine, there's nothing wrong with me its everybody else that's mad. And the hospital, let him do that……..”

5.2 Person centred system

5.2a. Person-centred support influences experiences

The participants expressed many positive accounts of receiving person-centredness. One participant felt her cancer treatment was positive and could not ask for a better experience: she received person-centredness within the NHS, the community, and personal relationships. The participant described herself as self-assured, needing to be in control and had prior knowledge (as a health professional) of health language, the cancer care setting and unusually said she always knew she would one day have cancer. She was a positive person and very likable (see appendix D4 T). This questions whether the PCS she received was due to the service being Cancer care as opposed to MH, or her ability to converse with professionals, and family, or whether the prior knowledge supported her to move through the process with self-autonomy and positivity. It is beyond the scope of this project to clarify whether everyone would receive the same positive experiences within that service.

The previous literature has shown that people from DAB experience higher levels of dissatisfaction when using services to support SM (Ghammari et al., 2023). Literature points to a lack of health language, knowledge, and negative attitudes, being factors to receiving PCS (Cooper et al., 2011: Pollak et al., 2010: Buyens et al., 2022). It is difficult to confirm whether a person is disagreeable due to poor experiences or receive poor experiences due to being disagreeable (Jensen‐Campbell et al., 2010), talked about in the Big five model (Feher & Vernon, 2021). The previous literature points to inabilities to engage due to lack of trust, suggesting disagreeable qualities (Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Theories such as Bandura’s self-efficacy, self-perception, and social cognitive theory (Bandura & Adams, 1977: Bem, 1972: Bandura, 2002) demonstrate that you need to show people how you expect to be treated, self-assurance, high self-efficacy and good boundaries are paramount, as it is evident in the way we hold ourselves and express ourselves and our needs, which leads to a self-perpetuating cycle of positive interactions (Canevello & Crocker, 2010).

The interviews highlighted the health funding inequalities between services, described by two people regarding the quality and experiences of cancer patients in comparison to MH (Appendix D.3 & D4) (Bowles et al., 2023).

This quote highlights the positive experience of cancer care

“It was all absolutely brilliant. I was given lots of information to take away in terms of leaflets. And the contacts for the breast care nurses were always contactable………..

(Appendix D.4)

5.2b. Self-autonomy influence experiences

The patterns which emerged through the story showed a large pool of the positive impacts of self-autonomy, as expected. However, the narratives highlighted that with choice often comes responsibility. There is a need to be well informed and possess the capability to self-advocate when making decisions about treatment and SM. Social exchange theory suggests a cost benefits analysis must occur to manage inner conflict of core values and obligations (Stafford et al., 2021). One individual had to sacrifice their usual medication for the wellbeing of their unborn baby; another participant felt burdened with guilt after making the choice not to remove her compression sleeve at work for fear of lymphedema symptoms, leaving her colleagues short staffed on the ground.

Long-term SM requires professionals and participants to formulate effective lifestyle interventions led from the participants (Bao et al., 2022). According to literature the main ingredients of SM are: self-autonomy, relatedness, and perceived capability (Powers et al., 2015), whereas long-term SM requires professionals and participants to learn effective lifestyle management for successful SM. The three main constructs needed for SM and motivation according to one study are feeling competent to achieve the goal, self-autonomy, and relatedness (Powers et al., 2015).

The following quote describes the burden and guilt the participant endures, from exercising choice, where it affects colleagues

“……….. I feel like I'm doing 50% of my job because I can't do clinics, well I say I can't, I choose not to in a way because I need to remove the sleeve and if I remove the sleeve, I risk the swelling increasing……………”

(Appendix D4)

5.2c Personality influences experiences

The emerging pattern during the stories pointed to the need to have wisdom and life experience of unsuccessful interactions. Personality development during adult life in response to living with LTC’s changed from feeling disempowered and vulnerable to proactive, tenacious, and self-assured. The narratives were different depending on the health-condition. Carers possessed a strong sense of altruism, finding strength to fight for the needs of loved ones, but not for their own health and wellbeing (Vitaliano et al.,2003). Individuals living with MH conditions reflected on the need to adapt and develop communication behaviours over the years to receive PCS (Marklund et al.,2020). An individual, living with Colitis disengaged from services after a difficult experience opting for private holistic care to access PCS. The six participants all mentioned the need for strength and assertiveness to access desired support, in line with previous literature (Hibbard & Greene, 2013: Chen & Yang, 2014: Williams et al., 2019):

The quote highlights that assertiveness and self-assurance increases the likelihood of the individual to receive the support they desire.

“I don't find it particularly difficult to talk to people about being depressed because I've dealt with it for a long time, so I think in some ways I've helped line managers to manage me because I've been able to say I need and that”. (Appendix D.3)

5.2d. Communication influences experiences

The patterns of positive communication accounts centered around deliberate and thoughtful communication strategies from people who had an understanding and a long history of both the health and social care system, as well as possessing substantial health language vocabularies, enabling them to converse with healthcare professionals and receive person-centredness in return. This supports the previous literature confirming health language and good communication skills increase the likelihood of receiving person centredness in healthcare, one of the interviewees sits in the low SES category, but over many years has overcome adversity and now sits on the panel of volunteers for Devon carers within MH Services (Schmidt et al., 2002: Epstein et al., 2005). The negative experiences highlight that people who cannot converse due to ill health, or lack of confidence do receive less person-centredness leading to poorer health outcomes, as shown in previous studies where communication has broken down from use of jargon and refusal from professionals to engage at the patient’s level (Levinson et al., 2010: Ferguson & Candib, 2002: Lee et al., 2002)

The following quote illustrates the poor communication when unwell, creates a barrier to patient activation and self-management.

“……..you have to be well enough to be able to talk in a way that you can talk appropriately. That is, you're not shouting or threatening or freaking out or panicking or demanding.

. So, if you're asking respectfully, but clearly and you've got patience, because it will take you ages, to get a response depending on the organisation………………….”

(Appendix D.1)

5.2e. Knowledge influences experiences

Actual and anticipated person-centred experiences were significantly more frequent when the individual had prior knowledge of health language and the ability to assert their needs in line with previous literature (Hibbard & Greene, 2013: Chen & Yang, 2014: Williams et al., 2019). The results indicate that knowledge is empowering; it is important to note the limitations of this subtheme, as all accounts came from one participant, who by their own admission felt they were a process driven person, who enjoyed the knowledge and structure of their treatment plan. Wider literature suggests that SM is rooted in self-efficacy. One component of self-efficacy is knowledge. Chronic conditions require a holistic approach, supporting several aspects of a patient multi-dimensional wellbeing (Holmes et al., 2019: Rogers, 1995: Taylor et al., 2018). The accounts did follow a positive experience; the lack of accounts from other participants may also indicate that they did not receive memorable knowledge which may have contributed to feeling unsupported.

The quote indicates how knowledge can enhance self-management.

“The oncologist… amazing man says, have you got your phone? and I thought, this is a really strange way to start a consultation. I thought he was going to tell me to switch it off, he said turn on your phone and put it here to record the conversation. This is really unusual because clinicians would usually be concerned that something may be brought from the past to the future, he said, Just record everything that I say, because you're going to forget it, there's going to be so much information, you're not going to retain it or you're going to get it mixed up …………

(Appendix D.4)

5.2f. Working in partnership with professionals

Previous literature describes the historic problem of patients being unequal in the patient / participant relationship, thus disempowering the individual to SM (Eklund et al., 2019). The person-centred model encourages individuals to actively engage in their treatment or service plan, requiring a holistic approach from services and community members to provide opportunities to SM their condition autonomously (Rogers, 1995: Taylor et al., 2018: Grover et al., 2021: Clark et al., 2018).

The data in this subtheme clearly showed how working in partnership, co-writing support plans, spending time revising treatment plans and listening to individuals’ experiences to meet patient choice where possible in a therapeutic alliance, showed an overwhelming improvement of quality of life which research supports (Gagliardi et al.,2021). Behaviour change theories, such as the Self-determination Theory, increases PA (Deci & Ryan, 2012: Powers et al., 2015).

The quote demonstrates how partnership can work for self-management. The individual writes known deterioration signs and symptoms which occur in an acute episode, along with remedies to prevent the individual from declining further, linked with self-autonomy results (4.3a).

“I can't remember what they call it exactly, but anyway, I got a support plan, a future support future support plan, they call it! And so, when we looked at it, they sent me a copy of it. We looked at it and I was like, oh my God, that's what's happening. It was like, I do that, and that happens, and in the support plan, it's like, what helps me? yes. And the brilliant thing is, they let me write my own support tips”.

(Appendix D.1)

5.3. Person-centred experiences in the community

5.3a. Community support influences experiences

The participants tell varying experiences and perceptions of community support. Firstly, the history and condition is a factor of community support and engagement. For example, one participant in her 60’s described herself as institutionalised and, therefore, felt comfortable in prescribed community groups. She felt hopeful that young people with MH could integrate fully into mainstream groups. Colitis appeared to be difficult to manage in several ways, people seemed to have a lack of understanding which caused avoidance of the participant. There were no appropriate uplifting groups, causing further isolation. Another participant described the lack of inclusivity for those who are immune compromised; limited options to meet in large groups in confined spaces were not appropriate. One lady with Cancer described an experience of friends rallying round, cooking meals, emotionally supporting, adjusting the running group to her needs throughout treatment, and she felt an overwhelming sense of love and support which gave her strength. Social support theory posits that those who engage in community are far more likely to engage in SM and experience improved QoL. This was evident with a participant who was diagnosed with Bipolar after her parents passed away as a teenager. Historically, she has gone private for MH care and lived an insular adult life, due to traumatic relationships. Once pregnant, she received a wealth of MH support for motherhood and was offered community support which she engaged in, and she said the hole in her heart has healed (Appendix D.3) This is supported in other studies (Heaney& Israel, 2008).

5.3b. Managing LTC’s at work

One lady described how she felt like a burden to colleagues. Her health condition prevented her from doing 50% of her role due to lymphedema, despite supportive work policies, colleagues, and reasonable adjustments, she felt internally conflicted and unable to be vulnerable and supported at that level. It did not align with her core values and beliefs, so she is currently being interviewed for another role which she can fulfil 100%. Another lady described how MH awareness has developed in cooperative companies, which now prescribes the Calm app and provides MH awareness training to reduce stress induced time off work, rather than compassion for MH suffering. A company went out of their way to make reasonable adjustments for one participant: the support and kindness enabled SM of Colitis, without the adjustments she would have left and been unemployed. These positive accounts of reasonable adjustments are crucial to maintaining employment. The participant who had an acute attack of ME, decided not to tell work, she described her recovery as a period of extreme self-determination. She went to work and came home and slept each night. On Friday she would come home and sleep until Monday morning, for 12 months, until she recovered. She did not want the stigma she had experienced elsewhere. The participant with long-term MH, describes herself as institutionalised: she feels she will never be able to have employment, despite volunteering consistently for years, she feels safe where she is protected by MH policies and support when needed. People from disadvantaged backgrounds are often told to find employment, but social support theory highlights that people require adequate policies, reasonable adjustments, and social support to sustain the role and protect people from distress and harm (Williams et al., 2004: Evans & Repper, 2000: Gariepy et al., 2016).

“The following quote highlights the perceived barriers to paid employment.

“They kind of let me be and I will tell them if like I'm really struggling that I can’t finish that piece of work, I need to hand it offer, or the amount is too………………….”,

(Appendix D1.)

5.3c. LTC’s impact on QOL

LTC’s create a significant layer of stress others may not comprehend. The cognitive bandwidth required to problem solve and adapt, as well as the impact it has on self-esteem, and anticipated perceived stigma and prejudice significantly impacts on QoL (Burgess et al., 2022). One lady described her cancer diagnosis as something she thinks about constantly, every niggle or breast change raises alarm bells, needing self-reassurance and the need to spend time rationalising (see Appendix D.4). Another participant described how her daughter’s heart condition created a daily battle against the school to access social support and to keep her safe, had created poor MH within the whole family (see Appendix D.6). A carer of her husband with COPD, spoke about the lack of support for them, no respite and her day to day living feeling like Groundhog Day, isolated from the community since COVID due to being immune compromised. She felt she had a loss of identity, confidence and fears her co-dependant relationship is detrimental to her wellbeing (see appendix D.5). Lastly, one participant spoke about being a target of stigma and prejudice, due to living in MH housing from neighbours which impacts her self-esteem. Self-efficacy is crucial for SM and is systematically destroyed by stigma and prejudice. There is a clear need to continue raising awareness and compassion within communities (Michalak et al., 2007).

The following quote describes how stigma and prejudice is experienced by a lady with MH issues. The neighbour never spoke to her again.

“I was chatting to a lady who lives in the street a few doors up chatting away, previously smiling, and saying hello and we were talking about animals and everything, having a lovely chat and she said where do you live? So, I said I lived here and she looked at me, she turned around and she walked off”

(Appendix D.1)

PCC is a theory of practice, along with self-determination theory is widely used to support QoL with success, demonstrated in these studies (Sarfo et al., 2023: Ntoumanis, 2021).

5.3d. LTC’s impact on loved ones

Often during diagnosis, expressing and processing one’s own emotions whilst protecting loved one’s feelings is a social constraint which often prevents open communication: professional support may be more appropriate to allow the individual to explore, process and work through difficulties without protecting others, (Mosher et al., 2013). Counsellors and supportive community support staff could play a pivotal role of providing medical crisis, humanistic support, reducing the burden on families. This is evident in other studies (Koocher et al., 2001: Feinstein et al., 2020). Moreover, it is essential to provide this to people from disadvantaged groups who are likely to receive less family support (Krause et al., 2018).

“I also have a bereavement counsellor because of my dad dying and I had bottled up a lot of grief………………………. She let me talk about work, life and then when Colitis came on the scene, she really researched which I was very impressed by and felt again that she cared. She just listened and validated, didn’t give advice”.

(Appendix D.2)

Chapter 6 Conclusion and Recommendations

6.1 Introduction

This study aimed to gain insight into the lived experiences of people with long-term health conditions, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds and Person-centred support. The data highlighted that previous power imbalances, stigma and compassion has improved in the community and healthcare, but there is much work to be done. The study shows that target improvements are required to support staff and participants to communicate effectively, there appears to be a need for individuals to be assertive, strong and possess the mental energy to consistently apply pressure to get their needs met: this is particularly difficult for people from disadvantaged backgrounds (Williams & Mohammed,2013).

6.2 summary of findings

Unequal power and health inequalities reduce successful management and further induced poor mental health for the individual and their families. Lessor known conditions attract much prejudice, creating social stigma.

MH has vastly improved for those who have experienced the post institution MH services, but for younger individuals accessing quality mental health is not possible, being forced to go private.

The study supported previous literature that personality, communication, and knowledge are significant factors impacting the likelihood of receiving PCS, and that these traits can be learnt and perfected overtime to improve the likelihood of receiving improved interactions in day-to-day exchanges.

Community support access had wide reached inequalities. The condition diagnosis influences the likelihood of community support and inclusive activities, linking back to stigma and social inequalities.

For those able to access employment, policies and cultural shifts have improved the experience of management work, large co-operations are attempting to reduce time off in stress by improving conditions and awareness of MH, for those from disadvantaged backgrounds, barriers to paid employment due to lack of appropriate support and reasonable adjustments is still prevalent.

The impact on QoL is vast and requires mental and emotional strength, isolation, and loneliness due to public lack of understanding for all conditions which also attracted stigma and prejudice

Cancer is an exception to the other themes and appears to attract compassion, significant PCS support from community and healthcare, however the limitation of this finding is that the participant was a health professional with substantial knowledge, high self-efficacy and by her own admission controlled the outcome where possible, there are many studies highlighting the barriers to cancer care and support for those from disadvantaged backgrounds (Kelly‐Brown et al., 2022).

6.3 current literature and practical applications

The data adds support to the previous body of literature, highlighting people from disadvantaged backgrounds are disproportionally least likely to receive PCS, impacting on motivation and self-efficacy to self-manage conditions successfully (Holding et al., 2020: Schmidt et al., 2002: Epstein et al., 2005). Research looking specifically at the cause of low SES groups not receiving PCS demonstrated that funding into specialist training and awareness, time barriers, Stigma and unconscious bias continues to be a problem (Moore et al., 2017: Entwistle et al., 2018). The researcher recommends that funding is allocated to training staff to skilfully engage with disadvantaged groups and targeted interventions for disadvantaged groups to learn effective communication skills and health literacy. Community psychologists could link with social prescribers to raise awareness and support inclusivity in mainstream community activities.

6.4 Limitations

Limitations of this study included researcher inexperience and possible biases. The data sample was small and included two people from disadvantaged backgrounds, future studies could include a larger sample.

6.5 Recommendations for future research

Further investigate the inequalities between cancer care service quality as compared to mental health, this was not within the scope of the research aims, but possibly a future research area, which may support reducing inequalities within healthcare and how to support mainstream community activities to promote inclusivity and manage complex needs.

6.5 Summary

The study examined the many factors involved in person-centredness within healthcare, community and personal relationships of people who live with long-term conditions, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The experiences of each participant gave valuable insight into person-centred benefits and the negative effects of non-person-centredness and what constitutes as positive humanistic interactions according to the participants.

References

Adams, W. C. (2015). Conducting semi‐structured interviews. Handbook of practical program evaluation, 492-505.

Ali, A., Scior, K., Ratti, V., Strydom, A., King, M., & Hassiotis, A. (2013). Discrimination and other barriers to accessing health care: perspectives of patients with mild and moderate intellectual disability and their carers. PloS one, 8(8), e70855. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070855

Allegrante, J. P., Wells, M. T., & Peterson, J. C. (2019). Interventions to support behavioural self-management of chronic diseases. Annual review of public health, 40, 127-146.

Allmark, P., Boote, J., Chambers, E., Clarke, A., McDonnell, A., Thompson, A., & Tod, A. M. (2009). Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: literature review and discussion. Research Ethics, 5(2), 48-54.

Angwenyi, V., Aantjes, C., Kajumi, M., De Man, J., Criel, B., & Bunders-Aelen, J. (2018). Patients experiences of self-management and strategies for dealing with chronic conditions in rural Malawi. PloS one, 13(7), e0199977.

Arboleda-Flórez, J., & Stuart, H. (2012). From sin to science: fighting the stigmatization of mental illnesses. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(8), 457-463.

Arifin, S. R. M. (2018). Ethical considerations in qualitative study. International journal of care scholars, 1(2), 30-33.

Bandura, A., & Adams, N. E. (1977). Analysis of self-efficacy theory of behavioral change. Cognitive therapy and research, 1(4), 287-310.

Bao, Y., Wang, C., Xu, H., Lai, Y., Yan, Y., Ma, Y., ... & Wu, Y. (2022). Effects of an mHealth intervention for pulmonary tuberculosis self-management based on the integrated theory of health behavior change: randomized controlled trial. JMIR public health and surveillance, 8(7), e34277.

Barnett, K., Mercer, S. W., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S., & Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 380(9836), 37-43.

Barron, G. C., Laryea-Adjei, G., Vike-Freiberga, V., Abubakar, I., Dakkak, H., Devakumar, D., ... & Karadag, O. (2022). Safeguarding people living in vulnerable conditions in the COVID-19 era through universal health coverage and social protection. The Lancet Public Health, 7(1), e86-e92.

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1-62). Academic Press.

Beresford, P. (2011). Supporting people: Towards a person-centred approach. Policy Press.

Blundell, R., Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., & Xu, X. (2020). COVID‐19 and Inequalities. Fiscal studies, 41(2), 291-319.

Bouchareb, S., Chrifou, R., Bourik, Z., Nijpels, G., Hassanein, M., Westerman, M. J., & Elders, P. J. (2022). “I am my own doctor”: A qualitative study of the perspectives and decision-making process of Muslims with diabetes on Ramadan fasting. Plos one, 17(3), e0263088.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage

Buchmann, J., Baumann, N., Meng, K., Semrau, J., Kuhl, J., Pfeifer, K., ... & Faller, H. (2021). Endurance and avoidance response patterns in pain patients: Application of action control theory in pain research. Plos one, 16(3), e0248875.

Bullen, B., Young, M., McArdle, C., & Ellis, M. (2019). Overcoming barriers to self-management: The person-centred diabetes foot behavioural agreement. The Foot, 38, 65-69.

Burgess, E. R., Reddy, M. C., & Mohr, D. C. (2022). " I Just Can't Help But Smile Sometimes": Collaborative Self-Management of Depression. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW1), 1-32.

Buyens, G., van Balken, M., Oliver, K., Price, R., Lawler, M., Battisti, N. M. L., ... & Venegoni, E. (2022). Cancer literacy-Informing patients and implementing shared decision making. Journal of Cancer Policy, 100375.

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., ... & Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of research in Nursing, 25(8), 652-661.

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating good relationships: responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 99(1), 78.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. sage.

Chen, D., & Yang, T. C. (2014). The pathways from perceived discrimination to self-rated health: an investigation of the roles of distrust, social capital, and health behaviours. Social science & medicine, 104, 64-73.

Chenoweth, L., Stein-Parbury, J., Lapkin, S., Wang, A., Liu, Z., & Williams, A. (2019). Effects of person-centered care at the organisational-level for people with dementia. A systematic review. PloS one, 14(2), e0212686.

Chlebowy, D. O., Hood, S., & LaJoie, A. S. (2010). Facilitators and barriers to self-management of type 2 diabetes among urban African American adults. Diabetes Educ, 36(6), 897-905.

Chlebowy, D. O., Hood, S., & LaJoie, A. S. (2010). Facilitators and barriers to self-management of type 2 diabetes among urban African American adults. Diabetes Educ, 36(6), 897-905.

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American psychologist, 54(10), 805.

Clark, U. S., Miller, E. R., & Hegde, R. R. (2018). Experiences of discrimination are associated with greater resting amygdala activity and functional connectivity. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(4), 367-378.

Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L., Carson, K. A., Bone, L. R., Larson, S. M., Miller, E. R., ... & Levine, D. M. (2011). A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. Journal of general internal medicine, 26, 1297-1304.

Cooper, M., Avery, L., Scott, J., Ashley, K., Jordan, C., Errington, L., & Flynn, D. (2022). Effectiveness and active ingredients of social prescribing interventions targeting mental health: a systematic review. BMJ open, 12(7), e060214.

Coventry, P. A., Fisher, L., Kenning, C., Bee, P., & Bower, P. (2014). Capacity, responsibility, and motivation: a critical qualitative evaluation of patient and practitioner views about barriers to self-management in people with multimorbidity. BMC health services research, 14, 1-12.

Dearnley, C. (2005). A reflection on the use of semi-structured interviews. Nurse researcher, 13(1).

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory.

Deslauriers, S., Roy, J. S., Bernatsky, S., Blanchard, N., Feldman, D. E., Pinard, A. M., ... & Perreault, K. (2021). The burden of waiting to access pain clinic services: perceptions and experiences of patients with rheumatic conditions. BMC health services research, 21, 1-14.

Drury, A., Payne, S., & Brady, A. M. (2020). Colorectal cancer survivors’ quality of life: a qualitative study of unmet need. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care.

DuBois, C. M., Beach, S. R., Kashdan, T. B., Nyer, M. B., Park, E. R., Celano, C. M., & Huffman, J. C. (2012). Positive psychological attributes and cardiac outcomes: associations, mechanisms, and interventions. Psychosomatics, 53(4), 303-318.

Eaton, S., Roberts, S., & Turner, B. (2015). Delivering person centred care in long term conditions. Bmj, 350.

Edvardsson, D., Fetherstonhaugh, D., McAuliffe, L., Nay, R., & Chenco, C. (2011). Job satisfaction amongst aged care staff: exploring the influence of person-centered care provision. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(8), 1205-1212.

Edvardsson, D., Watt, E., & Pearce, F. (2017). Patient experiences of caring and person‐centredness are associated with perceived nursing care quality. Journal of advanced nursing, 73(1), 217-227.

Eklund, J. H., Holmström, I. K., Kumlin, T., Kaminsky, E., Skoglund, K., Höglander, J., ... & Meranius, M. S. (2019). “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 3-11.

Eklund, J. H., Holmström, I. K., Kumlin, T., Kaminsky, E., Skoglund, K., Höglander, J., ... & Meranius, M. S. (2019). “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 3-11.

El-Etreby, R. R., & El-Monshed, A. H. E. S. (2019). Effect of self-management program on quality of life for patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nurs, 7(4), 657-663.

Entwistle, V. A., Cribb, A., & Owens, J. (2018). Why health and social care support for people with long-term conditions should be oriented towards enabling them to live well. Health care analysis, 26, 48-65.

Epstein, R. M., & Street, R. L. (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 9(2), 100-103.

Epstein, R. M., & Street, R. L. (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 9(2), 100-103.

Epstein, R. M., Fiscella, K., Lesser, C. S., & Stange, K. C. (2010). Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health affairs, 29(8), 1489-1495.

Epstein, R. M., Franks, P., Fiscella, K., Shields, C. G., Meldrum, S. C., Kravitz, R. L., & Duberstein, P. R. (2005). Measuring patient-centered communication in patient–physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Social science & medicine, 61(7), 1516-1528.

Esmaeili, M., Ali Cheraghi, M., & Salsali, M. (2014). Barriers to patient‐centered care: A thematic analysis study. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 25(1), 2-8.